Satchel Paige’s 1942 Kansas City Monarchs’ uniform featured the KC heart on the sleeve.

When reflecting on the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 60s, you might recall significant events that advanced the cause. What may not immediately come to mind is baseball and how a series of events in the sport initiated progress for African American rights. With Kansas City as the epicenter, a seemingly unassuming series of events brought black athletes and the movement for desegregation into focus.

In 1947, baseball legend and former Kansas City Monarch, Jackie Robinson, became the first African American to play in Major League Baseball. The historic event officially ended racial segregation in professional baseball. By joining the Brooklyn Dodgers, he broke the six-decades long color barrier that had sidelined black players to the Negro Leagues and barred them from Major Leage Baseball.

According to Bob Kendrick, president of the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum (NLBM), Jackie’s admittance to the Major Leagues was the spark that jettisoned the civil rights movement in America. Before Brown v. Board of Education, before Rosa Parks refused to move to the back of the bus, and before Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. appeared on the national stage, there was Jackie Robinson.

“Jackie’s breaking of the color barrier legitimately started the ball of social progress rolling in our country,” Bob said. “But Jackie’s professional baseball career began right here in Kansas City, with the great Kansas City Monarchs. So it was our city and the Negro Leagues that gave America arguably its greatest hero in Jackie Robinson.”

Not only was Kansas City the springboard for Jackie’s professional baseball career, it was also the birthplace of the first successful organized Negro League. On February 13, 1920, the Negro National League was formed by Rube Foster, owner and manager of the Chicago American Giants, and a coalition of seven other independent black baseball team owners. The historic event took place at the Paseo YMCA – just around the corner from where the NLBM operates today, Bob said.

The Kansas City Monarchs were one of eight charter members, and the only one owned by a white owner – James Leslie Wilkinson, affectionately known as “Wilkie.” Bob said, “he treated his players with great respect and dignity, and as a result, his players absolutely adored him.” With Wilkie’s connections to stadiums across the country, the Monarchs went on to have a 40-year legacy of greatness with only one losing season in their entire career. “They were a model baseball franchise,” Bob said. “They sent more players to the major leagues than any other Negro Leagues team.”

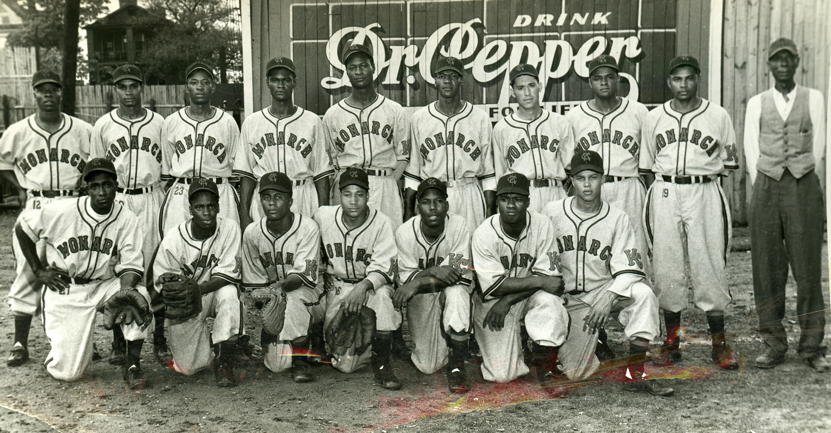

Kansas City Monarchs 1948

To be exact, 17 Kansas City Monarchs went on to the Big Leagues. Phil Dixon, Negro Leagues baseball historian, mused about the greats who made the team so extraordinary. These names included outfielder and National Baseball Hall of Famer Wilber “Bullet” Rogan, who is said to be one of the best pitchers and hitters in the Negro Leagues. Other Hall of Famers included Leroy “Satchel” Paige and John “Buck” O’Neil, who went on to become the first black coach in the Major Leagues. Another notable is Elston Howard, who holds the distinction of being the first black ball player for the New York Yankees.

For all of the greats whose names haven’t been lost to history, Phil said there are countless others who did not get their due honor such as John Donaldson. The pitcher whose record boasts more than 420 wins and 5,000 strikeouts didn’t make it into the Hall of Fame. As the author of the award-winning book, “Wilber “Bullet” Rogan and the Kansas City Monarchs,” and other titles, Phil believes Kansas City needs to know more about its rich baseball history. His goal is for the names of yesteryear’s local heroes, such as John Donaldson, to be known and remembered for many generations to come. “There’s so much here to celebrate that’s not being talked about and too many people who just don’t know, so I’ve taken it on as my job for the past 40 years to keep some names alive and to keep some history alive,” he said. The Monarchs were an iconic team – not just in Kansas City or in the Negro Leagues – but in baseball history. According to Bob, their touring schedule took them across the United States and even Canada to play minor league town teams. In a year, the Monarchs would play as many as 100 or more games. “They were beloved – not only in Kansas City, but around the country,” Bob said. “Their reputation certainly preceded them, and they delivered when they rode into those little towns. People got more than their money’s worth watching them play.”

As a result of their dynamite game play, the Monarchs gained fans, represented Kansas City, and showcased unsung talent wherever they went. “Sometimes I think it’s overstated what they did for Kansas City and understated what they did to bring the name of Kansas City out to the rest of the world,” Phil said. “When you get right down to it, jazz and the Kansas City Monarchs made this town what it is.”

Leroy Paige, Jackie Robinson, and Rube Foster

The Kansas City Monarchs were the center of African American civic pride, and the sentiment extended across racial boundaries throughout the city.

While the glory days of the Monarchs have faded into the timeworn pages of Kansas City history, remnants of the team’s heyday remain. Locals might be surprised to know their favorite way to show civic pride – the KC heart – was the Kansas City Monarchs logo. “If you look at the 1942 Kansas City Monarch uniform, you see that heart KC is prominently on the sleeve of the Monarch uniform.” Bob said. “For them, it represented the heart of America and the pride that they had being in Kansas City. It’s great to see that it has become this iconic symbol today.”

Additionally, Kansas City’s minor league team has been rebranded as the Monarchs, which has helped to build a fan base and bring more cultural relevance to the legendary Negro Leagues Monarchs team.

Currently, the NLBM is preparing to announce the details of its forthcoming yearlong celebration of the Kansas City Monarchs winning the very first Negro Leagues World Series. This year marks the 100th anniversary of the landmark event. “In essence, the Monarchs were our city’s first major professional sports team champion of any kind in 1924,” Bob said. “We think them winning that inaugural World Series is absolutely cause for celebration.”

If asked, Bob might say another cause for celebration is the NLB Museum’s plans for a brand new, 30,000 square foot facility, which will further cement the legacy of Negro Leagues Baseball and the Monarchs in Kansas City. The new museum will be built adjacent to the Paseo YMCA, which will be converted into the Buck O’Neil Education and Research Center. Bob said the new campus will serve as the gateway to the historic 18th and Vine jazz district and shine as the international headquarters for black baseball history.

While the history of segregation and racial discrimination in America are a troubling part of our past, the NLBM looks upon Negro Leagues history from a different perspective. “While many may think a walk through the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum will be a sad, somber story, it’s very much an uplifting story,” he said. “We don’t dwell on the adversity but look at what they did to overcome it. And while America was trying to prevent them from sharing in the joys of her so-called national pastime, it was the American spirit that allowed them to persevere and prevail. What’s not to love about that kind of story?”

Featured in the February 10, 2024 issue of The Independent.

By Monica V. Reynolds