Musical instruments evolve over time, as do social conventions that govern who is allowed to compose and perform music for those instruments. Though we sometimes wish the latter would advance more quickly — toward creating, perhaps, a more inclusive musical community — this evolution is inexorable.

This month’s French Organ Music Festival at the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception highlights both of these historical developments simultaneously. The Cathedral’s 50-rank Ruffatti pipe organ, installed during the church’s 2003 renovations, demonstrates the extent to which 19th- and 20th-century innovations have radically altered organs worldwide.

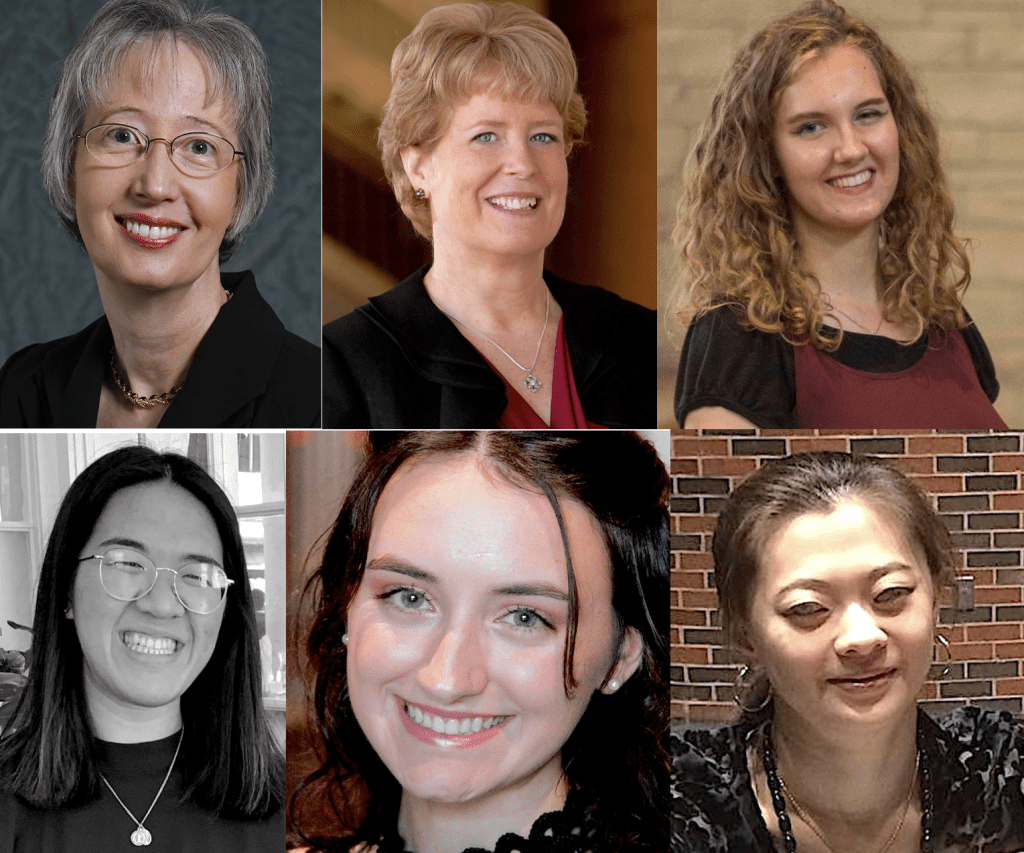

At the same time, this year’s program shows how profoundly the community of organ professionals is also changing: The artists for this Festival, possibly for the first time at any local professional organ recital, are all women.

Organized annually by the Cathedral and its director of music and principal organist, Mario Pearson, the Festival is co-sponsored by the Greater Kansas City Chapter of the American Guild of Organists.

“I’ve always worked very hard to include female performers,” said Mario, who established the French Organ Music Festival in 2013. “This year just happened to be a perfect storm. … More than half of the performers I identified were women anyway, so I said, let’s just add a couple more and make it all women.”

The lineup was not designed to make any kind of political statement. “What I’m trying to do is highlight local talent at the organ, and also to underscore that gender or race or ethnicity have nothing to do with the beauty of the music being presented,” said Mario, who was born in South Africa under apartheid and assumed his Kansas City post in 2006.

This year’s Festival includes two veteran area favorites, Jan Kraybill and Ann Marie Rigler, and four highly gifted student professionals: Isabel Alsum, Sherry Dou, Ann Pham, and Audrey Pickering.

Musical instruments have evolved at different rates historically. While the violin has changed relatively little over the last three centuries, the flute has grown in complexity from a single key (during the Baroque period) to 16 or 17 keys. Mozart’s piano had only five octaves instead of today’s seven.

The instrument that has perhaps changed most dramatically over the last two centuries is the pipe organ, which today includes — in addition to pipes designed to sound like instruments of the orchestra — some of the most advanced digital technology.

The new “orchestral” ranks (sets of pipes) were a product of the 19th century, when builders such as the renowned Aristide Cavaillé-Coll responded to composers’ demands for more complex colors. This French master builder crafted ranks that could mimic the flute, oboe, trumpet, strings, and a rainbow of other sounds, and he devised mechanical innovations to increase air pressure and to allow organists to make crescendos and decrescendos in ways they never could before.

These novelties continued into the early-20th century, chiefly in France, when the concern for “color” began to be seen in other art forms as well: among the Impressionist painters, the Symbolist poets, and even art-song composers and singers of the day.

“The French organ and its repertoire are all about tonal color, and the different characters or moods that those colors can evoke,” said Jan Kraybill, an organist, pianist, and clinician who has performed on nearly every French Organ Music Festival since its founding.

“French composers ask us as performers to combine and contrast those colors in unique ways. So, as an organist, when I’m setting registrations … I am trying to re-create the sounds that I’ve learned are typical of the instruments that French composers would have had at their disposal.”

The relationship between Cavaillé-Coll and 19th-century composers was “a symbiotic one,” Jan said. “You had this really innovative builder and then you had this hotbed, around Paris, of very creative composers who were ready to take advantage of whatever Cavaillé-Coll could provide them. … It was just an amazing explosion of creativity in the French organ school at that time.”

The innovations of this “French organ” are now a part of most organs made today, but digital technology is also an increasingly important part of contemporary organs. The instrument in Kansas City’s “Gold Dome” Cathedral was made by Fratelli Ruffatti of Padua, Italy, rebuilt from an organ the company originally installed in St. Paul United Methodist Church in Louisville, Kentucky.

“One of the things that I love about it is that it is such a diverse instrument,” Mario said. “It is literally four organs in one.” The Ruffatti has ranks of regular pipes, digital “alternatives” that can be combined with the pipes for richer colors, and ranks of orchestral voices that can be used in combination with the previous.

In addition, internationally renowned concert organist Hector Olivera gifted the Cathedral with ranks from Notre Dame and St. Sulpice Cathedrals in Paris, which he personally crafted from two of Cavaillé-Coll’s most significant organs. (Digitized ranks consist literally of recordings of pipes from other instruments.)

“You’re only limited by your imagination,” Mario said, adding that “because of the resonant acoustics in the Cathedral, it’s hard to tell the difference” between regular pipes and digitally recorded sounds.

The colors and features offered by today’s organs has, in turn, transformed the music being written for organ, even that for worship services. Whereas César Franck and Charles-Marie Widor and Louis Vierne paved the way, Olivier Messiaen and others in the 20th century investigated even further the infinite “hues” available on these new instruments.

Among the composers of our day who explored these colors was Rachel Laurin, a French-Canadian organist who died of cancer in 2023 and whose works Jan features in her portion of the Festival. “Rachel was so good at finding and manipulating colors on the organ,” Jan said, “and deciding what moods are prompted by which colors.”

In addition to being a stellar performer, Rachel was a superstar among women composers. “She was just such a bright light,” Jan said of the late artist. “You never forgot an encounter with her: She was so optimistic, so energetic, so full of humor.”

The Festival, which also features a wide range of audiovisual elements, has been livestreamed since the pandemic and continues to be. “Of course we want people to be here in person,” Mario said, “but for those who can’t be, we still have the livestream. And we have hundreds of viewers from all over the world who tune in.”

As in many areas of classical music, men still make up the lion’s share of top organ posts worldwide. But paths are being forged: Jennifer Pascual is organist and director of music of the magnificent St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York; closer to home, Marie Rubis Bauer is organist and music director at St. Cecilia Cathedral in Omaha.

For its part, the American Guild of Organists has created a task force toward gender equity among professional organists. “It’s still a male-dominated field,” Mario said, “but of course change happens slowly. … The fact is that we have six incredibly talented performers from here, who are women. … This is going to be a beautiful experience for the audience.”

The Thirteenth French Organ Music Festival takes place August 24th at the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception. For more information go to kcgolddome.org/get-involved/music-ministry or kcago.com/french-festival-xiii.

To reach Paul Horsley, performing arts editor, send an email to paul@kcindependent.com or find him on Facebook (paul.horsley.501) or X/Instagram (@phorsleycritic).

We asked each of the organists to answer a few questions about their lives with the organ and with French organ music.

Sherry Dou

At what age did you first begin organ study, and what in particular (or who) drew you to the instrument? What continues to draw you to it?

Having never played an organ before, I started organ lessons on a simple two-manual practice organ with a graduate teaching assistant as an elective at the end of my doctoral studies in piano in September 2021. It is God Himself who drew me and continues to draw me to the instrument.

What are some aspects (difficulties, challenges) of being an organist that people outside of the organ world might not fully grasp or appreciate?

I didn’t realize until 2023 how uniquely different each organ can be; otherwise, as a person with total visual impairment, I’m not sure I would have had enough courage to become an organist amid rapidly advancing electronic technology. On the other hand—perhaps both fortunately and unfortunately for organists—technique and discipline can be more easily obscured by the complexity of organ registration, which might help explain why the profession feels like shifting waters in terms of foundational playing skills.

What is unique or specific about the “French organ” or about “French organ music” (or school) that makes it different from other repertoires, and how does an organist approach it differently?

The development of the French organ and French organ music is closely tied to French church architecture, as well as to the role of the organ and music in the religious and cultural life of France throughout history. While rooted in specific stylistic traditions, French organ music allows for a degree of interpretive flexibility in performance and registration, which can vary depending on the instrument, acoustical environment, and the individual perspective of the organist.

Why did you choose the selections that you did? What do you hope the audience will take away from your contributions to the program?

I wanted to present a thoughtfully balanced and compact program within the required 20 minutes, with a gentle focus on music from Notre Dame, since this is the first year after the reopening of Notre Dame de Paris. As an organ and church music student at the University of Kansas, I have a special connection with the Cathedral’s organist titulaire, Olivier Latry. I hope my performance will bring the audience a sense of love and comfort in the midst of everything we are going through these days.

— — — —

Isabel Alsum

At what age did you first begin organ study, and what in particular (or who) drew you to the instrument? What continues to draw you to it?

I began studying at age 15. Having studied piano from an early age, what then drew me to the organ were the many levels of complexity in the sound, articulation, repertoire, and techniques of this instrument. What continues to draw me to the organ is the incredible legacy that the organ has throughout musical history.

Why did you choose the selections that you did? What do you hope the audience will take away from your contributions to the program?

I hope that the audience will enjoy hearing a work by the first female organist to sign a record contract, Jeanne Demessieux (1921-1968), as well as the enchanting prelude and fugue written in homage to Jehan Alain (1911-1940) by Maurice Duruflé (1902-1986).

— — — —

Jan Kraybill

At what age did you first begin organ study, and what in particular (or who) drew you to the instrument? What continues to draw you to it?

Like many organists, I began on the piano, and I still enjoy playing piano repertoire to this day. As a young teenager I played piano frequently in my family’s small church (Colby Presbyterian Church in Colby, KS). We were lucky to have a small pipe organ, built by Reuter, there. I will always be grateful for the day our long-time organist, Velma Lippoldt, offered to give me organ lessons, because that set me on a path that leads to the wonderful career I have today.

From my very first lesson with her — when she showed me that unlike the piano, an organ’s sound doesn’t stop, or even reduce in volume, until the player makes the decision to end it — I was fascinated. Later, it was the sense of accomplishment I felt when I achieved the proper coordination of hands and feet to successfully make music at this complicated machine. And still today, it’s those factors and more that keep me fascinated with this instrument — the power, and also the subtlety; the wide range of tonal colors; the sense of accomplishment when everything goes right; the variety among different pipe organs; the joy when someone tells me they were moved by my performance.

What are some aspects (difficulties, challenges) of being an organist that people outside of the organ world might not fully grasp or appreciate?

A challenge and also a joy, for me, is that every pipe organ is different from every other pipe organ. Each is custom-designed, both visually and tonally, for the venue and acoustic in which it resides. Each is a work of art; each has its own tonal palette of available colors with which to create more art. Some of them have one manual and some have two, three, four, five, or more. The number of keys on those manuals can be 61 notes, 56 notes, or somewhere in between. The design of the pedalboard’s keys can be flat or radiating or concave or some combination of those, and its range 32 or 30 or some other number of notes. The number of expression shoes can be different, depending on the organ pipes’ layout, and the number and location of other controls can be different. Etc, etc, etc! I often say that getting to know a new-to-me pipe organ is like getting to know a new person. You can read about a person in their bio or resume, and you can read about an instrument — but you don’t really know them until you’ve had personal experience with them.

Why did you choose the selections that you did? What do you hope the audience will take away from your contributions to the program?

I chose these composers because Mario told me he was planning to feature all female performers on this year’s French Festival. Since my segment will close the Festival, I wanted to play all female composers. Jeanne Demessieux is the name that first comes to mind when one things of female French organist/composers. She was a groundbreaker in all sorts of ways, and laid a strong path for we organists (of any gender) to follow: she was a prize-winning performer and composer, she was one of the first female artists to tour internationally, and she was the first female organist to sign a recording contract, among many other accomplishments.

I’ll play two of her works based on Gregorian chant melodies, which seemed fitting for the setting of the Catholic Cathedral. Rachel Laurin was a French-Canadian composer of our own time; she died just two years ago, at age 62, of cancer. (Jeanne Demessieux was also taken from this earth too soon — she died of cancer too, at age only 47.)

I’ve chosen to open and close my segment of the Festival with works by Laurin. The opening, a set of three short pieces, is full of virtuosity and good humor, starting with a piece for pedals alone, then a piece about hummingbirds in flight, and finally a piece about mockingbirds that pokes a bit of fun at we organists. The closing piece of the Festival, fittingly titled “Finale,” was premiered by Laurin in 2017. It is a virtuosic piece that celebrates this instrument and its repertoire, and the people who make it possible.

— — — —

Ann Theresa Pham

At what age did you first begin organ study, and what in particular (or who) drew you to the instrument? What continues to draw you to it?

I began playing the organ at age 14, though I never studied it seriously until the summer before I started college. I am drawn to serve others through what I know and love, namely sacred music, which includes the organ.

What are some aspects (difficulties, challenges) of being an organist that people outside of the organ world might not fully grasp or appreciate?

Being an organist usually entails more than just showing up to play. Many may not appreciate the behind-the-scenes service, teamwork, and leadership skills that are essential to being a successful church musician.

What is unique or specific about the “French organ” or about “French organ music” (or school) that makes it different from other repertoires, and how does an organist approach it differently?

One specific thing out of many: from French Classic repertoire to 20th century works, most French organ music is based upon the centuries-old tradition of Gregorian chant. It would behoove organists to familiarize themselves with the chant repertory, so as to more fully understand and perform the organ works well.

Why did you choose the selections that you did? What do you hope the audience will take away from your contributions to the program?

Litanies is an all-time favorite, Variations sur Lucis Creator follows quite nicely, and the first movement from the Passion Symphony is very descriptive and exciting to play/hear! I hope the audience will explore the lesser-known works of Jehan Alain, as well as the other movements of the Passion Symphony.

— — — —

Audrey Pickering

At what age did you first begin organ study, and what in particular (or who) drew you to the instrument? What continues to draw you to it?

I first began studying the organ when I was six years old. I love the orchestral nature of the organ! There are so many different sounds and colors to experience!

What are some aspects (difficulties, challenges) of being an organist that people outside of the organ world might not fully grasp or appreciate?

It takes a lot of coordination to play with all four limbs! It also takes a creative mind to find the correct sounds and colors for each piece of music.

What is unique or specific about the “French organ” or about “French organ music” (or school) that makes it different from other repertoires, and how does an organist approach it differently?

Dr. James Higdon, professor of organ at The University of Kansas, talks about how French music is color-dependent. With French music you really must find the right sounds to bring the music to life!

Why did you choose the selections that you did? What do you hope the audience will take away from your contributions to the program?

I love the French composer Louis Vierne! I performed the entire Second Symphony for my final Masters Recital at KU this past spring and each movement showcases a variety of sounds from the organ. Vierne’s organ symphonies have such a broad emotional range. From bold and dramatic to longing and beautiful to fun and exciting. I am excited to take the audience on a memorable musical journey!

— — — —

Ann Marie Rigler

At what age did you first begin organ study, and what in particular (or who) drew you to the instrument? What continues to draw you to it?

I began my organ studies at age 13, three weeks after hearing César Franck’s Chorale in E major at the conclusion of my first organ recital. Ever since then, I’ve been drawn to the organ for the ease with which it handles counterpoint, for the range of tone colors available on even relatively small instruments, and because the organ is a wind instrument that does not require the player to concentrate their attention on intonation. (Having spent two years attempting in vain to tune my flute against the dozen other versions of B-flat issuing from the instruments of my fellow flautists in the Rolla Junior High School band, I was absolutely elated to discover how I could “play the flute” on different ranks of flute stops without ever having to tune to anyone else.)

What are some aspects (difficulties, challenges) of being an organist that people outside of the organ world might not fully grasp or appreciate?

Instruments are not uniform in their dimensions, layout, or tonal capabilities. An organist must select their music on the basis of whatever the instrument at hand can execute, and becoming acquainted with an unfamiliar instrument takes time. Your responsibility as a player is to let the instrument do its job to the best of its ability.

What is unique or specific about the “French organ” or about “French organ music” (or school) that makes it different from other repertoires, and how does an organist approach it differently?

French organ music is exceptionally prescriptive with respect to timbre. If an instrument’s tonal resources cannot honor a composer’s intentions, then you have to ask whether performing that piece on that organ is fair to the music, the composer, the instrument, and the audience.

Why did you choose the selections that you did? What do you hope the audience will take away from your contributions to the program?

Jehan Alain is my favorite composer for the organ after Johann Sebastian Bach. Given the musical heritage of Roman Catholicism, I selected three pieces that place chant melodies in a variety of contexts while showcasing a wide array of tone colors. I hope that the music will offer the audience moments of reflection and renewal as the summer draws to a close and we anticipate the busy Fall season ahead.

Featured in the August 9, 2025 issue of The Independent

By: Paul Horsley