Each Black History Month, the same national figures are highlighted: Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, Rosa Parks. Meanwhile, the lives of local Black citizens whose work helped build and sustain communities remain obscured by time.

However, an ongoing collaboration among the Local Investment Commission (LINC), Kansas City Public Library (KCPL), and the Black Archives of Mid-America (BAMA) has worked to address that gap through the Kansas City Black History Project. What began as a small poster project at LINC has evolved into an ambitious annual public history record of Black Kansas Citians who shaped local neighborhoods, institutions, and civic life.

The collaboration began around 2010, following an early effort by LINC to recognize national figures during Black History Month. Its focus soon changed to local Black Kansas Citians, and it has been that way ever since. The project highlights the contributions of six individuals every year. Each annual edition includes a small booklet and a set of posters featuring a photograph and a short biography of those selected for the year’s focus.

Bryan Shepard, LINC; said the shift toward local history has made the project more meaningful for the community. “Focusing on Kansas City gave it more community pride,” he said. “Nothing like this had really been done on a local level.” Bryan noticed the public’s immediate willingness to embrace the project. “We saw the posters in the community at grocery stores, doctor’s offices, churches, and lots of our schools,” he said. “We’ve seen the impact that these posters in Kansas City were having early on in the city. It raised awareness and provided educational opportunities.”

By 2012, LINC had partnered with the Kansas City Library to introduce more comprehensive historical research and perspective. “We were sitting in a meeting room at the library, looked around, and there were four white guys talking about who to feature in Kansas City Black History Month,” Bryan said. “We recognized we needed a subject matter expert on this and immediately thought of the Black Archives.”

Today, each organization brings a distinct role to the partnership. The KCPL Missouri Valley Special Collections staff conducts research, writes the biographies, and locates historical images. Meanwhile, BAMA reviews the content and ensures historical accuracy. Finally, LINC pulls it all together by overseeing the design, printing, and large-scale distribution of materials throughout schools and community sites. Dr. Carmaletta Williams, BAMA; said the collaborative structure has been essential to the project’s credibility. “Everyone in this collaboration verifies the information,” she said. “We are telling the truth, and we are particular about who gets included.”

As for selection criteria, featured individuals must be deceased, must have verifiable documentation of their work, and must have an identifiable photograph. By featuring individuals from many backgrounds and professions, the project presents a fuller picture of Black local history. Jeremy Drouin, Kansas City Public Library; said, “We want the people we select to be diverse in the types of contributions they have made to Kansas City. There’s definitely a focus on jazz, Negro Leagues Baseball, and barbecue. Those are important, but there are also many other contributions in health, architecture, education, law, and the arts.”

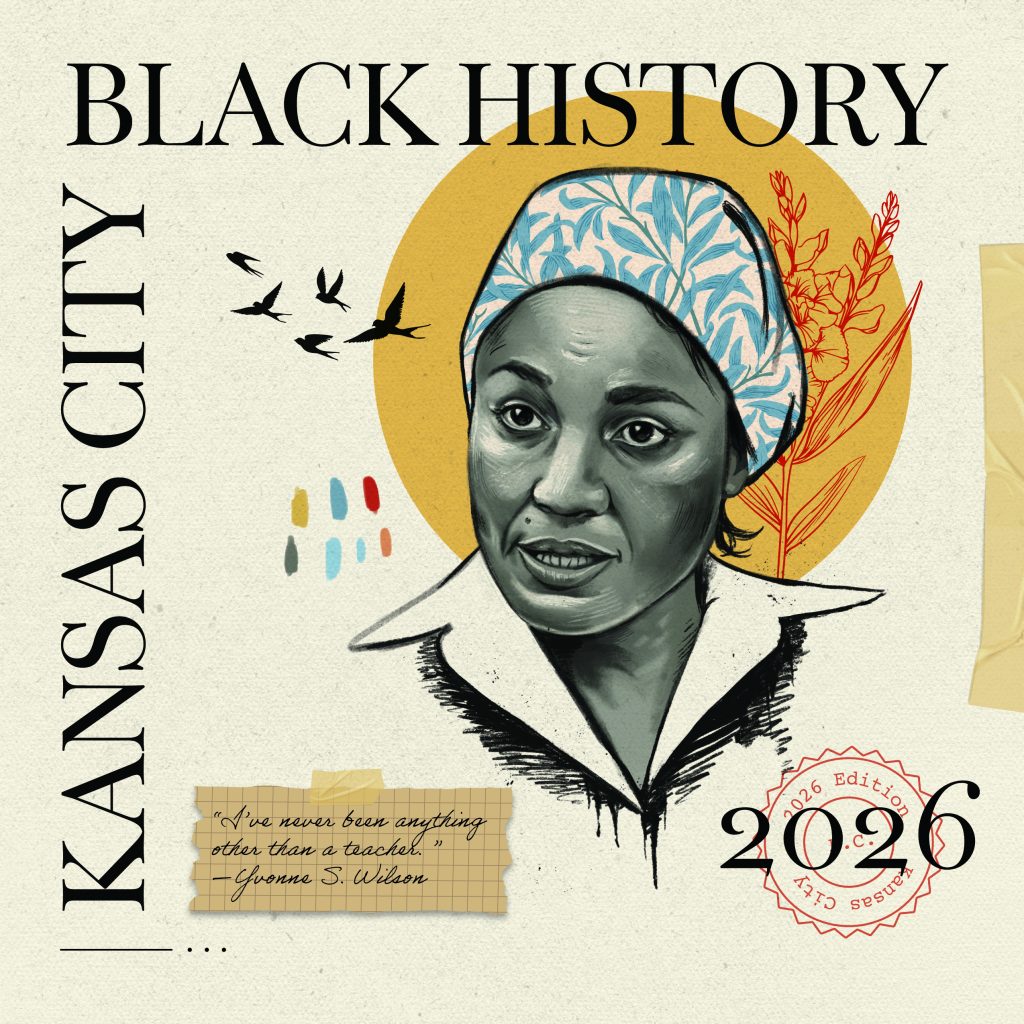

This year’s honorees are Carl M. Peterson, physician; Henry Perry, restaurateur; Henry V. Plummer, clergyman; John Dennis Preciphs, community activist; Lucille Jeanette Bacote, musician; and Yvonne S. Wilson, educator. The Kansas City Black History website states that this year’s individuals, “embody the American spirit of resilience in the face of oppression. Each carved their own path to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, leaving an indelible mark on our city.”

From the start, education has been a central goal of the project. Materials are distributed through library branches, schools, community centers, and churches across the metro area. Teachers frequently use the posters and booklets in classrooms during Black History Month. Bryan noted that LINC’s network also plays a major role in that reach. “LINC has over 50 Caring Community sites, mostly based at schools,” he said. “We can put these materials directly in front of students.”

Interest in the project has also extended beyond Kansas City and its classrooms. Through the years, the organizations have received requests for the posters and booklets from across the country and even internationally. “We’ve had requests from people in Nova Scotia and small towns in Tennessee with no more than a few thousand people because once one church had it, every church wanted it,” Jeremy said.

In 2021, the project reached a new milestone with the launch of kcblackhistory.org, a digital platform where expanded biographies and educational resources are featured and collected. “With the booklet format, we’re limited to about 200 words,” Jeremy said. “The website allows us to write much more detailed biographies. It can be very difficult to summarize the accomplishments and contributions of a person and their life and career in 200 words.”

The site also hosts lesson plans and archived programming related to Black history in Kansas City. Bryan said this extends the project’s reach beyond the local area, which is how many out-of-towners discovered the materials through online searches such as “Black history posters.”

Also in 2021, the partners produced a special compilation volume that included more than 90 biographies, along with essays from civic leaders reflecting on Black history in Kansas City. The publication received recognition from the American Association for State and Local History, the Jackson County Historical Society, and an award from the Missouri Library Association for Best Local History Project of 2021.

As the current year’s edition moves from the printer into libraries and schools following Martin Luther King, Jr. Day, the partners said the work continues. The Kansas City Black History Project, they say, will remain an ongoing collaborative effort recorded with a commitment to ensure Black Kansas Citians are represented in the city’s documented history. For Dr. Carmaletta, the project’s impact is easy to see in how people engage with the materials. “People want to hold them, share them, and talk about them,” she said. “History becomes alive.”

Featured in the February 7, 2026 issue of The Independent

By: Monica V. Reynolds