Since September of 2016 the Black Repertory Theatre of Kansas City has performed in schools, churches, storefronts, community centers—and sometimes even theaters. “Give us four walls, a bathroom, and an outlet, and we can make theater,” said Damron Russel Armstrong, founding artistic director, with a laugh. From the downtown Arts Asylum to the Warwick Theatre, from Paseo Academy to Metropolitan Community College and the Bruce R. Watkins Cultural Center, during its first decade Black Rep performed in more than a dozen venues.

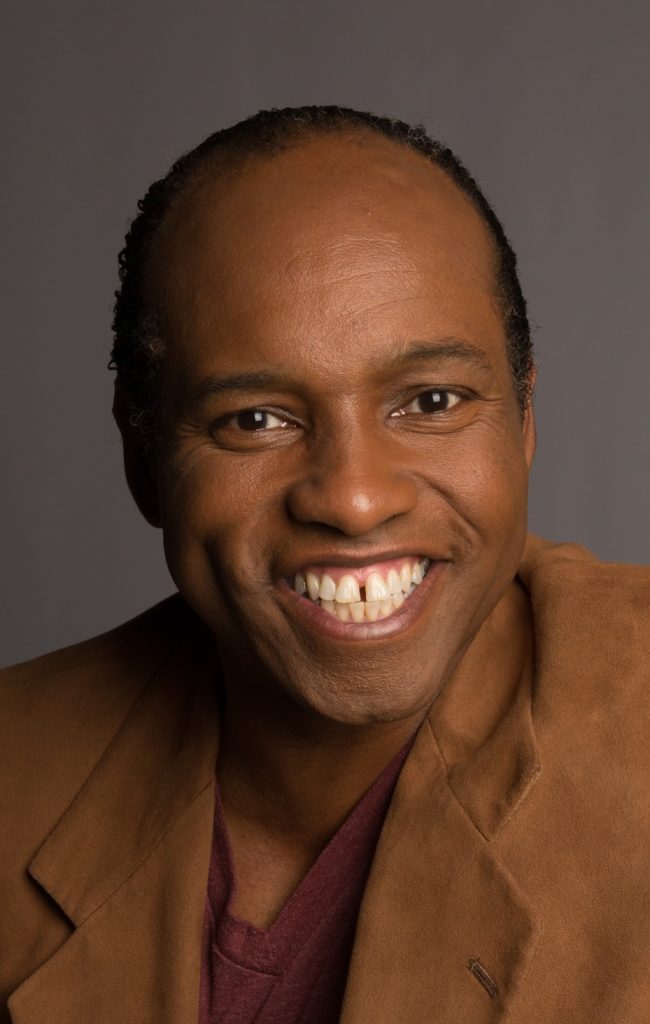

And as long as you double-checked the venue before you left the house, you were in for a treat: With Damron in charge, good theater always gets made.

But it was not their wish to remain nomadic forever. “Art should be accessible,” Damron said, of the admitted advantages of performing in a variety of community spaces. “But people also like the familiarity of knowing where their favorite theater is going to be.”

Now, at long last, the BRTKC is to have a permanent home. As it celebrates its 10th anniversary this season, in the coming weeks the company will take up residence in the Boone Theater—a classic 1924 structure at the center of the 18th and Vine Historic District that is being thoroughly renovated: at an estimated cost of $8.7 million. “It becomes a home,” said Damron, who after 20 years as a successful theater professional in New York moved back to Kansas City to start this company. “Kansas City will finally be able to associate the Black Rep with a venue.”

The company also announced the appointment of its first executive director, Christopher Peacock, a visionary leader with more than 20 years of experience in nonprofits, education, and community engagement.

“Christopher’s leadership is exactly what the BRTKC needs at this pivotal time,” said Board Chair Tracy E. Jamerson, adding that the appointment will “ensure that the company thrives as a cultural anchor now and in our future home at the historic Boone Theater.” Christopher also noted in a statement that the company is “a powerful platform for storytelling, community building, and cultural expression.”

In addition to being Black Rep’s 10th anniversary, 2026 is also the centenary of Black History Month, which was established (initially as Negro History Week) by historian Carter G. Woodson in 1926.

The Boone opened as the New Rialto Theater, and during the past century it has served a wide range of uses. In 1930 it was renamed to honor John William “Blind” Boone, an influential early ragtime pianist from Missouri. During the 1940s and ’50s the building contained a restaurant, a market, and—at various times—offices, shops, and even a hotel. During the 1950s and ’60s it was predominantly a military armory.

The new Boone will have two primary arts residents: the Black Rep and the new Black Movie Hall of Fame. It will also contain DistrKCt Multimedia and will feature office and storefront space.

Spearheaded by a partnership called the Vine Street Collaborative (which includes Shomari Benton, Tim Duggan, and Jason Parson), the project has tapped local design firms and architects; the construction is by PARIC, LLC, a company that specializes in historic renovation and reuse.

Born in Windsor, North Carolina, Damron moved to Kansas City with his family in the late 1960s when his father, Richard, signed with the Kansas City Chiefs. Damron caught the theater bug early and by age 17 was already a member of Actors’ Equity Association. He moved to New York in the 1990s, returning frequently to appear on Kansas City stages, and he performed with major companies around the United States.

Damron might have stayed in New York had it not been for the death of Trayvon Martin in 2012 and the subsequent acquittal of his killer, George Zimmerman. “It made me stand back and say, What sort of practical application can I take from this situation … the senseless death of this child?” he said. “Who knows what contribution he could have made to society?”

One of Damron’s driving passions is highlighting Black contributions to American life and culture, and at that moment he realized that within his own profession there were Black artists whose gifts were not being fully recognized, including those in his hometown. Kansas City was at that time one of the few American cities without a professional theater that “gave a platform for African American voices to be spotlighted,” Damron said. (To be sure, some local companies were producing work by Black artists, and around this time KC Melting Pot Theatre was also being formed.)

Providing a forum for Black Americans to tell their stories has become more critical than ever. And as everyday discourse becomes increasingly polarized, theater can play a distinct role in bringing us together. “Theater holds a mirror up to society,” Damron said. “It makes it more palatable for people to have conversations about difficult topics.”

BRTKC’s brilliant first production, Dreamgirls in Concert (fall of 2016), catapulted the company forward almost immediately; the extraordinary Shon Ruffin, now recognized as one of the region’s most gifted artists, made a resounding impression in the role of Effie.

As the community sat up and took notice, early seasons brought acclaimed productions of Lydia R. Diamond’s Stick Fly, Charles Fuller’s A Soldier’s Play, George C. Wolfe’s The Colored Museum, and musicals such as Memphis, Ain’t Misbehavin’ and Blues in the Night.

The company has increasingly attracted national attention, thanks largely to Damron’s persistence and connections, and it has scored recent coups with fresh-off-Broadway productions of Keenan Scott II’s Thoughts of a Colored Man (2023) and Jocelyn Bioh’s Jaja’s African Hair Braiding (2025). During the current season, BRTKC will also reprise The African Company Presents Richard III, Once on This Island, and Five Guys Named Moe.

The design team for Boone renovations has been sensitive to the needs of the resident companies—even as it has made the theater adaptable as an event space and preserved the aspects that give the structure its historical landmark status.

“We had lots and lots of conversations about what was needed,” Damron said. Crossover space, plenty of room on the sides of the stage, and lighting that can illuminate the entire space. Plus dressing rooms, a green room, and technological amenities: “All of the things that a theater in Kansas City has to have,” he said.

Black Repertory Theatre of Kansas City has already enriched our theater community immeasurably, with plays that give voice to underrepresented Americans but speak to all—produced by artists who heroically bring Black representation to the fore. The power of theater to change hearts should never be underestimated. “The experience of being in a live theater can be life-changing,” Damron said.

—By Paul Horsley

For information about upcoming productions of Black Repertory Theatre of Kansas City, go to brtkc.org. For information about the Boone Theater, its history, and its offerings, go to boonetheaterkc.com. To reach Paul Horsley, performing arts editor, send an email to paul@kcindependent.com or find him on Facebook or X/Instagram (@phorsleycritic).