Members of the Marsalis family have made such regular visits to Kansas City that listeners might not realize that one of the most famous, and most fabulously gifted, scions of this venerable family has yet to make a Kansas City solo debut.

This month, the Bach Aria Soloists will present trumpet virtuoso Rodney Marsalis, the youngest of the quartet of most-famous Marsalises and cousin to Wynton and Branford, on a program of chamber music for trumpet, soprano, violin, cello, and organ.

Rodney Marsalis

“No one plays absolutely beautifully all the time,” said no less of an authority on the trumpet than Wynton, “unless you’re my cousin Rodney.” Wynton, who has won nine Grammy Awards (in jazz and classical categories), brings his Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra to the Harriman-Jewell Series on a fairly frequent basis, and his brother Branford (best known as a former saxophonist-bandleader on The Tonight Show), has appeared on the Folly Jazz Series, most recently in 2019.

Their late father, Ellis, was still touring a decade ago, and as recently as 2011 he brought his quartet to The Folly. (He passed away in April 2020.)

Rodney was right there in the middle of it from the start: He was raised in the heart of New Orleans’ music scene, began the trumpet at age six, and later studied with Ellis at the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts, a rigorous school for gifted students. Ellis became a mentor for Rodney, as he had been for so many artists from the region: a strict but loving taskmaster who always had sage musical advice.

“When I was a kid, if there was a question about anything… we would literally get in the car and drive over there to Hickory Street,” Rodney said recently. “And sit there at the kitchen table and talk to Ellis. He was like the intellectual center for all of us.”

By age 11, Rodney was an accomplished enough performer to take up lessons with Wynton, who was all of 17 at the time. “But Wynton was a very serious 17-year-old,” Rodney said. “He showed me the basics of what I needed to do on the trumpet,” he said, adding with a laugh: “But he was my older cousin, so he didn’t have to be nice to me during lessons. … He really kicked my butt.”

The Bach Aria Soloists: Sarah Tannehill Anderson, Elisa Bickers, Elizabeth Suh Lane, and Hannah Collins

Rodney was drawn to orchestral playing, and his next teacher was George Jensen, who introduced traditional classical principals (among his students were Wynton and Terrence Blanchard) even in the face of criticism. “I remember at one point someone told him, Why are you teaching all these little Black kids? They’re not going to be classical musicians,” Rodney said.

But it was during these years that Rodney began to hear what great trumpet-playing could be. “Terrence would play these amazing solos,” he said. “That’s what I grew up hearing: I saw Wynton doing it, I saw Terrence doing it. … Those were my earliest influences of what you should be able to do on the trumpet.”

It paid off: During his high school years, Rodney was invited to the summer sessions of the Tanglewood Music Center, where he received the Seiji Ozawa Award for Outstanding Musicianship. It was a sweet new world for him.

“You are around people who do what you are passionate about, and you’re all together on this beautiful campus in the Berkshires,” Rodney told musicologist Demarr Ray Woods. “It was an inspiration being around those kids. I made lifelong friendships there.”

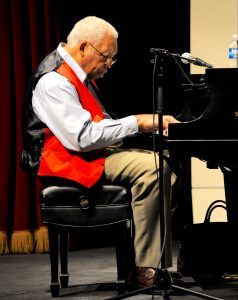

Ellis Marsalis, Jr.

Later, at Boston University, Roger Voisin prepared Rodney for the rigors of orchestral auditioning, which eventually got him into the New Orleans Symphony. When that orchestra folded, he returned to the East Coast for even more intensive training: first with the Boston Symphony’s Charles Schlueter, then at the Curtis Institute, where he spent three intensive years with Frank Kaderabek, legendary former principal trumpet of the Philadelphia Orchestra.

“Lessons at Curtis were so serious that I had to start practicing that night in order to be ready for the next week,” Rodney said. He subsequently won prestigious posts at San Diego Symphony, the Colorado Symphony, the Richmond Symphony, the Tenerife Symphony, and the Barcelona Symphony.

It was in Spain that Rodney faced the worst racist incident of his life, one that nearly cost him his life and made it into The New York Times. The brutal beating at the hands of Barcelona undercover police, “officially” declared a case of mistaken identity, resulted in a formal apology from the chief of police and an apology, by the Governor of the State, in front of the Spanish Parliament.

“It took about a year and a half to recover, with physical therapy and Tai Chi,” Rodney said. In addition to suffering post-traumatic stress, he added, “I couldn’t lift my arms, without pain, for a really long time.”

All was not lost: When Rodney moved back to Philadelphia, he met the woman who would become his wife: a physician with whom he now shares a rustic suburban life with the couple’s five-year-old daughter. “I always tell my young students, when bad things happen you don’t know what good is going to come out of it. If that hadn’t happened to me in Spain, I would never have come back here, and I would not have met my wife.”

Rodney devotes most of his time to leading the Rodney Marsalis Philadelphia Big Brass, which usually consists of: Benjamin Goldman, Natalie Dungey, Steven Vogel, Courtney D. Jones, Adam Gautille, Rodney Marsalis, Gregory Freeman, Terry Everson, Martin McCain, Natalie Brooke Higgins, and Marty Erickson.

Rodney now serves as principal trumpet of the Chamber Orchestra of Philadelphia, but he devotes enormous energy to running the Rodney Marsalis Philadelphia Big Brass, which he founded in 2006. Its wide musical range (which includes classical, jazz, and popular arrangements) offers a welcome change from his orchestra years.

Nevertheless, Rodney is pleased with his achievements in the classical realm. After all: he toured the world, performed with the great conductors of our time (including Leonard Bernstein, Michael Tilson Thomas, Gerard Schwarz, James DePreist, John Williams, and Jesus Lopez-Cobos), and took part in 30 recordings, on the Decca, Naxos, Koch Classics, and Albany labels.

The orchestra world is small, and through the long and winding road of Rodney’s career he kept running into Elizabeth: First when he was a Boston University Tanglewood Institute student (“I just remember she was a really nice person”), then when Elizabeth was on tour with the London Symphony Orchestra, and finally at a Leonard Bernstein memorial they both took part in.

It was much later, at an Arts Midwest Conference, that they realized they were both engaged in similar efforts: Elizabeth’s Bach Aria Soloists was as unique in its artistic profile as Rodney’s Big Brass, and as they exchanged notes over lunch they realized it would make sense to actually collaborate.

“We’ve always said to each other, we should do something together,” Elizabeth said, adding that: “We spent a whole afternoon talking about not-for-profit versus for-profit,” Elizabeth said. “And finally I just said: How about you coming here?”

Elizabeth hopes that her organization can continue to be a conduit for inclusive programming: Recent concerts have included works by Black women such as Florence Price and Jessie Montgomery and by the Indian-American composer, Reena Esmail. The group has also performed and commissioned works by Asian and Asian-American composers such as Narong Prangcharoen. “I hope we can be advocates for change” in the classical canon, she said. “I think it’s time.”

—By Paul Horsley

BAS Presents: An Evening with Rodney Marsalis will take place on April 29th at Village Presbyterian Church. For tickets, go to bachariasoloists.com.

To reach Paul Horsley, performing arts editor; send an email to paul@kcindependent.com or find him on Facebook (paul.horsley.501) or Twitter/Instagram (@phorsleycritic)