We often say that an actor on stage or screen has “leonine grace,” or eats like a ravenous wolf, or moves with reptilian stealth. What you might not realize is that “animal work” is actually a part of nearly every actor’s professional training: studying the movements, positions, and sounds of different creatures to expand one’s psychological and emotional range.

Sometimes that training takes overt expression, as when characters in Aristophanes become birds or frogs, or when the comic figure of Bottom is transformed into a donkey in A Midsummer Night’s Dream. But more often the goal is to use aspects of animal or even insect-like behavior to expand the possibilities of portraying a human character.

Stephanie Roberts

“Actors discover things that they might not have,” said Stephanie Roberts, an actor-director and specialist in physical theater who is also a professor in the Master of Fine Arts Theatre program at the UMKC Conservatory. “It shakes them outside of the habitual way that they’ve learned the lines… they discover new meaning because they’ve embodied that character in different ways.”

Stephanie encourages students to observe real animals, “because there are particular rhythms that we can learn by watching them.” After this, an actor can “go back and keep that discovery, without necessarily playing the animal itself.”

This sort of training was pioneered by the Russian-born Maria Ouspenskaya, a student of Konstantin Stanislavsky who taught it to “method acting” guru Lee Strasberg of the famous Actors Studio. “It teaches you about yourself and your own instrument, brings an awareness of yourself,” Stephanie said.

This method often begins small, with insects, birds, and fish. “So how do you become a centipede, with many, many legs?” Stephanie said. “How do you become a bird, but you have arms and legs?” Observation of these creatures becomes crucial, she added, “looking at the rhythms, the mannerisms, the essence of movement of those creatures.”

Stephanie Roberts is proud of her photogenic canine companion, Kali.

Students then move to animals: in Stephanie’s classes, dogs, cats, and squirrels. “Those are three animals that are very different from one another, as far as their rhythms go, but are familiar to us.”

Students can go outside of Grant Hall at UMKC to see squirrels, “and usually when I ask them to be dogs and cats, I can tell which students really have dogs or cats at home.”

All this can make for interesting family conversations. “So that when you go home for Thanksgiving,” Stephanie said, “and your parents ask what you did in graduate school, you can say you were lava, or you were a centipede.”

Animal work often has direct applications in theater.Heart of America Shakespeare Festival’s recent production of The Tempest featured animalistic creatures for two of the leads.

“In our interpretation, Ariel was of the air and Caliban was of the earth,” said Festival Director Sidonie Garrett. “So, if I were to make each of those things an animal, what would they be?”

Mary Traylor’s costume designs helped enhance a sort of birdlike quality for Ariel and an amphibious embodiment for Caliban: without literally turning the characters into creatures. “They are not human, so we have to find inspirations in the animal-like qualities,” Sidonie said.

In most instances, however, the goal of animal work is to create characters that are more fully human, by tapping into aspects of an actor’s persona that are buried within. Marlon Brando famously used the concept of a gorilla in preparing for the role of Stanley in Elia Kazan’s A Streetcar Named Desire.

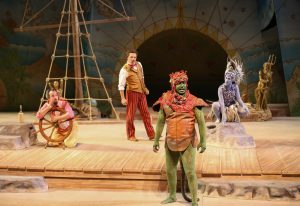

Joshua Gleeson (Trinculo), Kris Stoker (Stephano), Keenan Ramos (Caliban) and Chelsea Rolfes (Ariel) performed in a co-production of The Tempest by Heart of America Shakespeare Festival and UMKC Conservatory Division of Theatre.

“Sometimes we get stuck in our own box,” said Sidonie, adding that animal work was part of her own training as an actor, and remains so in acting programs everywhere.

“When you expand your viewpoint and your sources of inspiration… creatures that are alive and move can be helpful in fulfilling, three-dimensionally, what you’re trying to create.”

This topic has a slightly different spin in theater for young people: Children almost instinctively love animals, and these exercises can be a tool for getting them out of their shells. “Our classes for younger kids tend to be very centered on animals,” said Amanda Kibler, education director at the Coterie Theatre, which often produces works with actual animal characters.

“It’s a great way into acting, and into theater: to start off by acting like an animal, because it forces you to stop being yourself,” said Amanda, whose master’s degree is in theater for young people. “I can’t be Amanda if I’m acting like a penguin, so I have to be a penguin. It’s a good shortcut to get you out of yourself and into just a visceral reaction.”

Animal depictions form an important part of any theater for young people, and The Coterie is no exception. “Animal images are a huge part of the training in our theater school,” said Producing Artistic Director Jeff Church, adding that Amanda’s training “makes her an expert in animal class pedagogy!”

Amanda Kibler with her dog, Bart

For example, the Hero Pets class being offered this spring “has completely sold out,” Jeff said. “you can’t get in it even if you wanted to. … We’re all about animals.”

Young people usually don’t grasp the idea of mimicking animals for abstract purposes until they reach their early teens, and thus Amanda’s work for children differs markedly from the techniques she uses in classes for adults.

“With my college students, I’m using it to push them a certain way,” Amanda said, “to help them get out of their own heads: How do you move? … So it’s a means to an end. Whereas with my younger students, getting to be a dog is the end. That’s what they want to do: They want to pretend to be a dog, or a cat. It’s the end itself.” (Pete the Cat, a Coterie production,runs through May 22nd.)

Some theater companies engage in a different kind of “animal work,” finding it helpful to have an actual animal around during rehearsals and even performances: not so much to emulate as to take comfort from the beast. Karen Paisley, founding artistic director of the Metropolitan Ensemble Theatre, frequently keeps her own pet, a natural “theater dog,” on the premises of the Warwick Theatre.

Chelsea Rolfes performed as Ariel, costumed here as The Harpy, with John Rensenhouse as Prospero, in the co-production of The Tempest with Heart of America Shakespeare Festival and UMKC Conservatory Division of Theatre.

The young people in the company’s recent production of Oliver! fell head-over-heels for Poppy, Karen’s two-year-old Golden Retriever-Saint Bernard-Great Pyrenees mix. “Poppy became a rallying-point for them,” said Karen, who adopted the affectionate pup from Great Plains SPCA. “She became their dog, and attended nearly every rehearsal.”

But Karen also believes in the effectiveness of conventional animal work in theater, and she often uses it in her own direction.

“It removes limitations,” she said. “When I’m coaching actors I’ll often say, Take the ceiling off your head. … As long as you are limiting your choices, you are going to be stuck with whatever you have already, instead of embracing everything that is possible. And that’s what acting is all about.”

—By Paul Horsley

To reach Paul Horsley, performing arts editor; send an email to paul@kcindependent.com or find him on Facebook (paul.horsley.501) or Twitter/Instagram (@phorsleycritic).