Mixing musical genres can be tricky business. When José “Pepe” Martínez and Leonard Foglia joined forces to create what they called “the first mariachi opera,” there were no clear models and no assurances that it would register at all. The result, Cruzar la Cara de la Luna (with music and lyrics by Martínez and book by Foglia), received its premiere at Houston Grand Opera in 2010.

It turned out to be such a winning amalgam of styles that has garnered numerous performances worldwide — Austin, San Francisco, Minneapolis, New York, even Paris. It arrived on the Lyric Opera stage this March 7th through the 9th, sung primarily by operatically trained singers who sounded quite at home in the full-bodied vocal style we associate with ranchera/ballad singers.

Calling the piece an opera might limit its reach: Cruzar has the feel of a piece that could fit into the repertoire of any theater company that produces musicals. Critic Anthony Tommasini, in his review in The New York Times of the work’s 2018 New York City Opera run, called the piece a “rich, honest opera” — and then added “or call it a chamber opera, or a music-theater piece. It hardly matters.”

To be sure, Cruzar is operatic in many ways. Employing solo “arias,” duets, trios, and quartets, it trades in outsized but fundamentally human emotions: undying love, family rancor and crisis, deathbed regrets. It exists in a version with orchestral accompaniment, but Kansas City audiences were lucky to hear it performed in its original mariachi version — with the Los Angeles-based Mariachi “Los Camperos,” whose instrumentalists (on violins, trumpets, guitars, harp) also served as a sort of opera chorus.

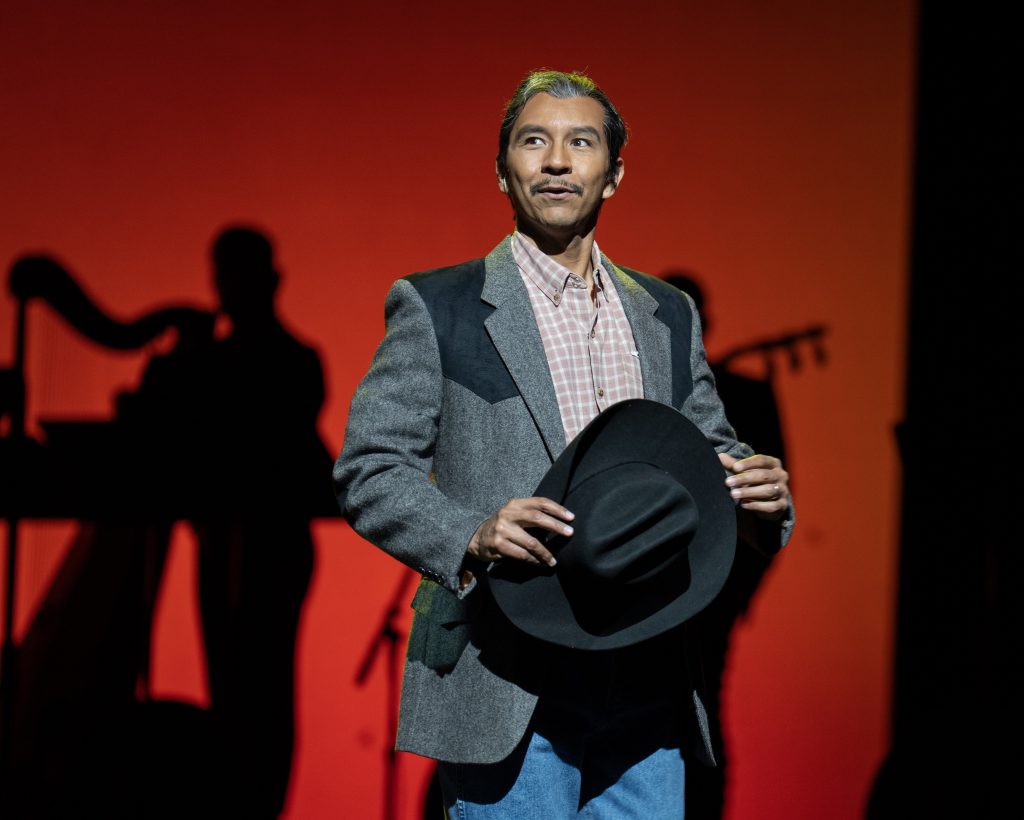

At the center of the story is Laurentino, a role sung with remarkable ease and naturalness by baritone Octavio Moreno. We first meet him as a bedridden septuagenarian, reminiscing about his wife and Mexican-born son in Mexico while being serenaded by his American-born son, Mark (bass-baritone Federico De Michelis).

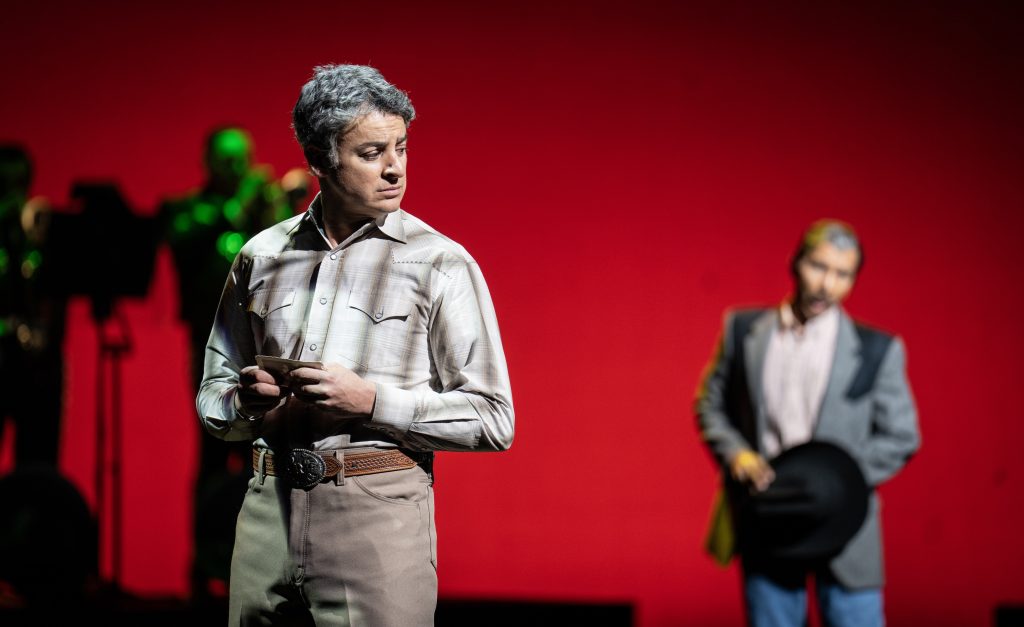

The dementia-plagued Laurentino, who has spent most of his life in the United States, imagines that Mark is his Mexican son, Rafael (tenor Daniel Montenegro), whom he has not seen decades — just as he later mistakes his American-born granddaughter, Diana (soprano Bethany Jelinek) for his late wife Renata (Cecilia Duarte).

We also see Laurentino as an ambitious 25-year-old in Mexico, marrying Renata and joining his compadre, Chucho (Miguel de Aranda), in a duet about the allure of north (“Diez veces más”): where a man can live in a house 10 times as large, be 10 times the man … as in Mexico.

Later, after most of the men have left to find work in the United States, Renata and Lupita (Vanessa Alonzo) lament living in a “village without men,” where “the children need their fathers.” (The earlier setting is evidently during the braceros program, which brought a large number of men from Mexico to fill labor gaps during World War II and its aftermath.)

Through a tragic twist of fate, the embittered Rafael is left behind in Mexico, and it is Laurentino’s yearning for reconciliation — introduced early in the piece — that provides the primary conflict. Daniel Montenegro sang with a fetching tenor (Lyric audiences heard him in La traviata in 2022), delivering a great deal of heft in his relatively short time onstage. Particularly moving was the tumultuous duet “Los ojos de tu madre/mi madre,” in which we see Laurentino and Rafael drawing closer.

The dual allegiance to two families, two “homes,” is a very real part of the immigrant experience for many, and this gives special tristesse to the final quartet, “Mi hogar.” There are, significantly, frequent references to, and visual evocations of, the monarch butterflies whose traversal from south to north and back again serves as a metaphor for immigration itself.

Martínez’ and Foglia’s opera treats its subject with subtlety, wit, and charm. But Cruzar also “clicks” through the clarity and forcefulness with which it shows that beautiful singing traverses genres. “Good technique is good technique,” said Lyric General Director Deborah Sandler Kemper after the Saturday performance, in a talkback with artists and the Mexican Head Consul to Kansas City, Soileh Padilla Mayer.

Indeed, when listening to the best Mexican singers of the past (Amalia Mendoza, Silvia Pinal, Jorge Negrete) one realizes how little distance stands between the pathos of ranchera heartbreak and the high tragedy of grand opera.

— Paul Horsley

For tickets to upcoming Lyric Opera performances, including the four productions of the 2025-2026 season, see kcopera.org or 816-471-7344. To reach Paul Horsley, performing arts editor, send an email to paul@kcindependent.com or find him on Facebook (paul.horsley.501) or Twitter/Instagram (@phorsleycritic).