Dr. Alex Red Corn

The era of the American frontier is a history passed down through generations. Yet, a particular chapter we don’t often hear of is stained with injustice. According to some, the ripple effects of European colonization and the Native American boarding schools they erected can still be felt among Indigenous communities. Within the walls of these institutions, the identities, language, and culture of Native people were stripped away. Today, Native communities are making strides to revive their culture and heal the past. Simultaneously, educators are working with Native leaders to address the inherent biases in the education system and build bridges with the broader community.

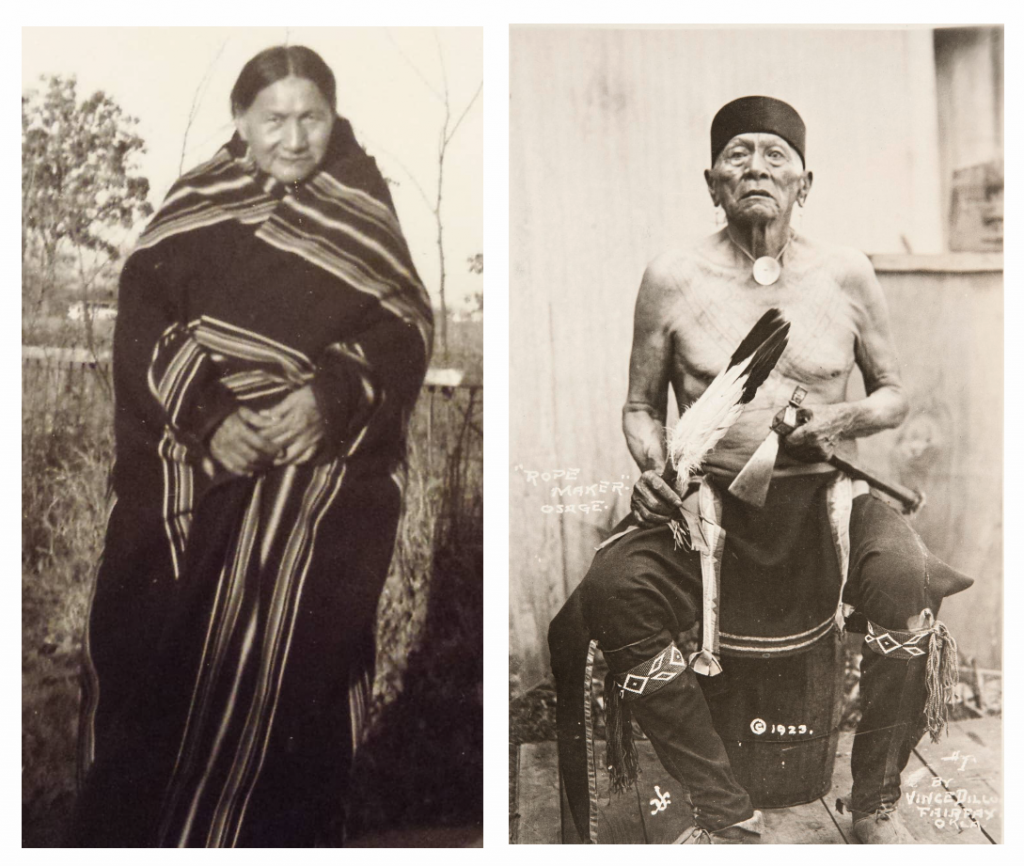

To understand the changes taking place at present, it helps to first look to the past. Osage professors Dr. Alex Red Corn (Kansas State University) and Jimmy Lee Beason II (Haskell University faculty) share a belief in the importance of preserving Indigenous cultures and bringing about related reforms within the education system.

Jimmy Beason, who teaches Indigenous Studies, asserts that Indigenous culture on the frontier was systematically eroded. Following the American Indian Wars, also known as the American Frontier Wars, the United States adopted a strategy to suppress potential uprisings. Natives were forced onto reservations, which Jimmy referred to as, “open air prisons.” Eventually, the Bureau of Indian Affairs pushed Indigenous people to undergo a forced assimilation where they began to live like European farmers.

Additionally, they forcibly separated Native children from their families. The children were enrolled in boarding schools, which, contrary to their name, were anything but traditional educational environments. Although the schools provided vocational training, their main objective was to eradicate Indigenous heritage from young minds and assimilate Native youth. “There was this idea of Native people being savages and uncivilized,” Jimmy said. “They were being slowly turned into an ‘ideal American’. The schools emphasized individualism, concepts of private property, Christianity, and patriarchal notions of family.”

These boarding schools were notoriously harsh environments where children endured mistreatment, and many lost their lives. According to Jimmy, those institutions created a legacy of trauma that continues in today’s Indigenous communities. “The so-called boarding ‘schools’ really damaged a lot of our people,” he said. “It’s a huge healing process for us right now to understand why we deal with the things we do in our communities. There was a lot of trauma that they endured and passed down to their own families. The only way they knew how to handle their children is what they experienced themselves, which was very abusive and degrading. So in some of our communities, we’re dealing with a lot of different types of dysfunction.”

In an effort to heal and reclaim their heritage, Jimmy’s ancestral community, the Osage, have initiated a cultural and language revitalization program. “Today, we’re trying to reclaim those things that were taken, and learning language, getting reconnected with our spirituality, and trying to ensure our children know these things so they’re able to view themselves with a sense of pride, honor, and dignity that the children in these institutions’ so called boarding schools didn’t receive.”

Despite the scarcity of fluent speakers, the Osage have developed their own writing system, using symbols that signify sounds, and the language is evolving. Additionally, the tribe offers ribbon work classes and hosts ceremonial dances like the Inlonschka during the summer, which serves as both a warriors’ dance and a celebration of the first-born son.

According to Jimmy, the dance teaches values such as mutual respect, community, and support, which can be passed down to future generations, including his three children. For Jimmy, the dance is also a testament to Osage fortitude. “It brings a sense of pride and morale,” he said. “Despite everything that’s happened to us, the colonization, and also the Osage Indian murders that took place in the ‘20s, we are still doing these things. I think that speaks to our resiliency and also speaks to the way in which these (cultural) things need to be protected.”

Beyond the revival of cultural traditions, Jimmy and Alex say educational reforms are needed. According to Alex, to understand the importance of these reforms, it’s essential to examine the historical roots of educational institutions. Alex is an Educational Leadership Coordinator for Indigenous Partnerships at Kansas State University. He posits that universities, including Kansas State University, were originally designed to serve the incoming settlers. This inadvertently sidelined Indigenous culture and wisdom. “They were institutions of research for white settlers,” he said. “And you have generations of academic foundations being built entirely on Eurocentric ways of developing knowledge and understanding the world. What got completely pushed aside was Indigenous ways of knowing and understanding the world.”

Alex went on to share that, in recent decades, a broad community of Indigenous scholars have played a pivotal role in challenging inherent biases in academia and reevaluating academic approaches. “There’s a collaborative ecosystem of people across the state and across institutions that are a part of this,” he said.

Qualitative research methodologies have been central to this shift. Unlike traditional scientific approaches, qualitative methods delve into the complexities of human experience. Alex asserts this approach recognizes there isn’t a single pathway to knowledge. “It’s more complex than just one form of knowing science,” he said. “If we don’t confront those problematic histories and confront how they still kind of live on, then we can’t change our systems to improve how they operate in society and how they serve communities.”

Additionally, Alex explained that mainstream education often falls short in addressing the specific needs of Native communities. While mechanisms exist for Native students to gain mainstream workforce skills, Native language, cultures, and history often take a backseat. Despite the presence of tribal colleges and universities catering to this need, Alex says the majority of Native students find themselves navigating the offerings of state public schools and universities.

However, Native communities’ elders are strategically at work to safeguard their heritage for future generations. “What you’re seeing is this movement of resurgence,” he said. “Native people aren’t always trying to reclaim the past. They’re also looking at how they can adapt.”

Despite these efforts, Alex acknowledges there is an absence of structured methods for facilitating Native education. This has resulted in a high turnover rate as educational leaders are left to learn on the job. As a result, Alex spearheaded the Educational Leadership Graduate Certificate Program, available through Kansas State University. The program is geared toward providing a comprehensive curriculum that challenges conventional Eurocentric approaches. To that end, the program encourages critical thinking about existing systems and their impact on Indigenous communities. It also equips future education leaders with practical skills to initiate change at a programmatic level.

Graduates are not only prepared to navigate the complexities of Native education but to also prepare non-Native students to engage meaningfully with Indigenous communities. Alex said this program paves the way for a new generation of leaders, fostering understanding, respect, and collaboration among diverse communities. He likes to call it, “cultivating conditions for collaboration into the future.” Alex said, “If you have Natives and non-Natives learning more about Native cultures, tribal governments and all these things, then they’re more prepared to work across those lines.”

Meanwhile, Jimmy Beason also advocates for reforms, including educating children about the historical significance of the land upon which their school stands. He proposes integrating lessons about the land’s past, emphasizing events both pre- and post-1900, as many schools currently neglect the history of Native people beyond that year. “We’re always framed in this historical context where we don’t have any bearing on the present,” he said. “And it’s always about this kind of romanticization of Native people, you know, like ‘back in the day.’ But today, we’re trying to pay the bills like everyone else, while also trying to maintain our culture and our tradition.”

Moreover, Jimmy strongly advocates for schools to discontinue the use of Indian mascots. “I think that only perpetuates stereotypes,” he said. “Those are just the caricatures of what non-Native people think Native people should be or are.”

In closing, Jimmy emphasized the necessity of having more Native educators and advisors to increase representation and provide an accurate education about Native people. He pointed out the prevalence of misconceptions, saying that, as the most marginalized group in the country, Indigenous people remain overlooked and unaddressed in discussions. Within the education system, crucial aspects of Native history and culture are often omitted, leaving people to rely on inaccurate portrayals in movies or mascots.

In summary, Dr. Alex Red Corn and Jimmy Beason’s insights call for a more accurate and balanced representation of Indigenous heritage in education. Native educators play a critical role in fostering understanding and dismantling stereotypes that perpetuate historical injustices. Moreover, by having their voices heard and included, Native American educators can lead the way to a more inclusive, accurate, and respectful portrayal of Indigenous cultures, which can be a bridge for societal understanding and mutual respect.

Featured in the November 11, 2023 issue of The Independent.

By Monica V. Reynolds