Musical inspiration often thrives under unusual circumstances. Mozart composed La clemenza di Tito after being yanked reluctantly from his progress on The Magic Flute, to take part in a highly politicized operatic commission for the Prague coronation of Leopold II as King of Bohemia; political agendas notwithstanding, it remains one of the great operas of the era.

Haydn forged a completely new symphonic style during his employment at the remote Austro-Hungarian court of the Esterházy family. “No one in my vicinity could make me lose confidence in myself or bother me,” he wrote, “and so I had to become original.”

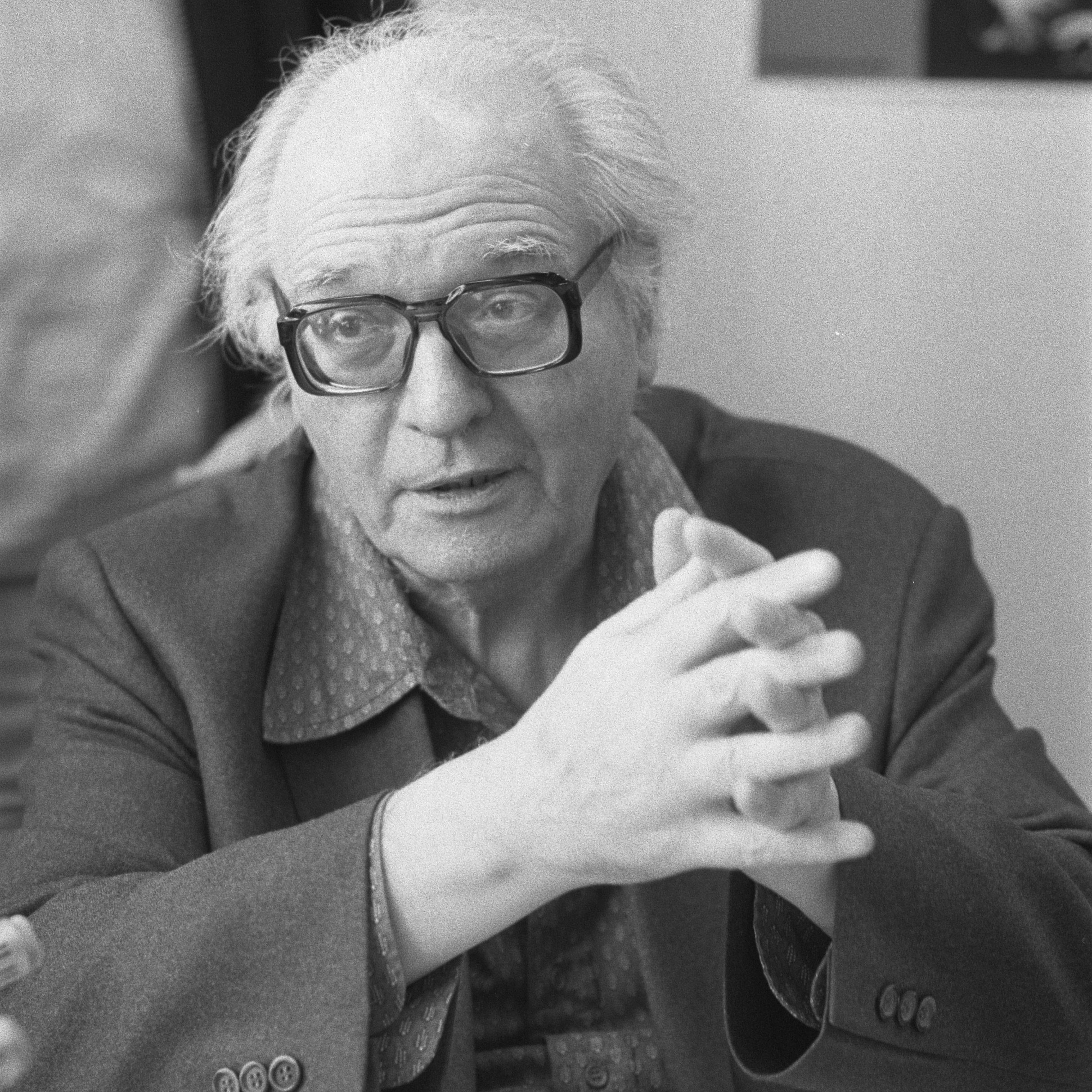

One of the most striking examples of circumstance dictating art took place in 1941, when the French composer Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992) joined three fellow inmates at the Nazis’ Stalag VIII-A prison camp to create one of the most memorable experiences in the history of Western music.

Having been called to duty in the French army in 1939, the 31-year-old Messiaen was taken prisoner in May 1940 and joined several thousand French and Polish inmates at the Stalag in Görlitz/Zgorzelec on the German-Polish border. (Eventually the camp would house Belgians, Soviets, Brits, Italians, Slovaks, Australians, New Zealanders, and even Americans.)

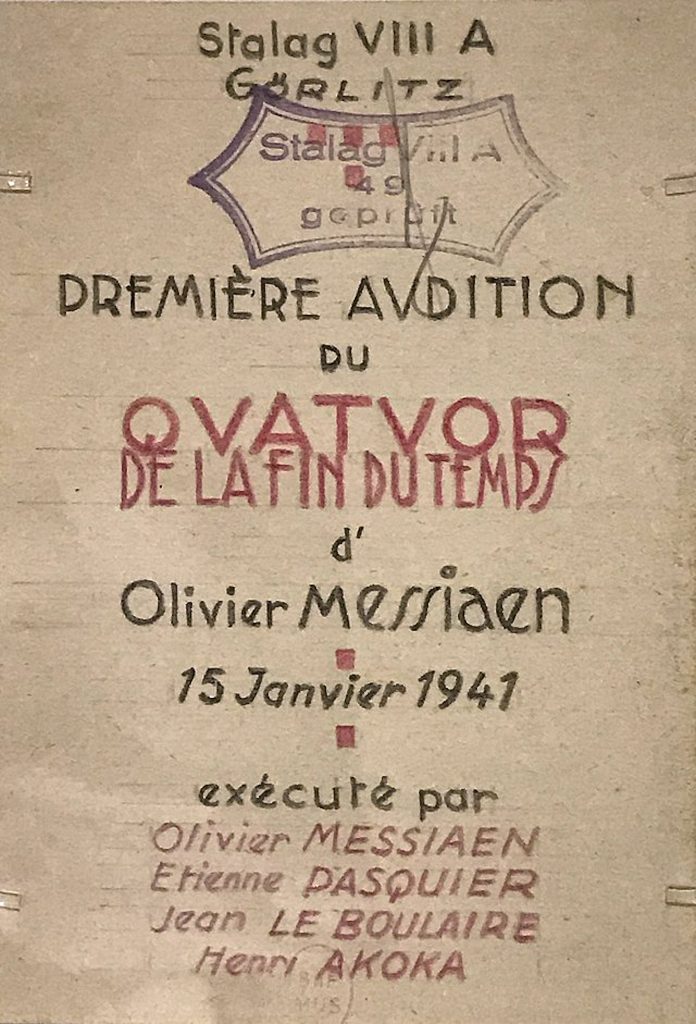

When German officers in charge discovered that they had a famous composer in their midst, they provided him with score paper, pencils, erasers, and solitude to compose. Messiaen had meanwhile learned of three other prominent French musicians at the camp, which had been designed for a few hundred but would ultimately house thousands. The Quartet for the End of Time was thus scored for clarinetist Henri Akoka, violinist Jean Le Boulaire, and cellist Étienne Pasquier.

Messiaen himself played on the camp’s run-down upright piano at the premiere, which took place on October 15, 1941 in front of several hundred inmates — “among which were gathered all the different classes of society: laborers, intellectuals, career soldiers, medics, priests,” Messiaen wrote. “Never before had I been listened to with such attentiveness and understanding.”

Messiaen was released from the camp less than a month after the premiere and repatriated to an occupied France, as eventually were the other musicians.

This July in Kansas City, the musicians of Summerfest undertake this most demanding of 20th-century milestones, in the opening concert of the series’ 32nd season. The Messiaen joins a “quartet” of large-scale masterworks — by Vaughan Williams, Beethoven, and Dvorák — each of which anchors one of the four July programs. The rare performance constitutes only the second appearance of the Quartet on the series.

The Quartet is a staggering achievement: an eight-movement, hour-long catalogue of 20th century chamber-music techniques that bursts with color, virtuosity, and extroverted spirituality. Messiaen’s own descriptions of each movement include angels, rainbows, birds, trumpets, gongs.

“It’s one of those pieces in which you’re always wondering, Am I really worthy to play this?” said cellist Alexander East, who during the regular season is assistant principal cello of the Kansas City Symphony and who performed the Quartet on the series in 2002. “My intuition said it was a good time to do it again.”

“It’s a difficult piece technically, but it’s also a hard piece emotionally, beyond the technical aspects,” said clarinetist Jane Carl, a UMKC Conservatory professor and longtime Summerfest artistic advisor, who has performed the Quartet several times. “There’s so much involved in playing it, and there’s so much you want to bring to it.”

In addition to the “mythology” that builds up around a piece created in a prison camp, the work contains apocalyptic evocations from the Book of Revelation; a collection of complex palindromic rhythms drawn from ragas of classical Indian music; and a large dose of the composer’s signature bird songs — the collecting of which was to occupy Messiaen for a major portion of his life.

Jane and Alex are joined by pianist Melissa Rose, who took part in the 2002 performance, and violinist Anne-Marie Brown, who is new this time around. “It’s a complicated piece of music to unwrap,” said Jane, whose part includes a whole movement devoted to solo-clarinet reiterations of transcribed bird songs.

The composer inscribes his score thus: “In homage to the Angel of the Apocalypse, who lifts his hand toward heaven, saying: ‘There shall be time no longer.’ ” Although it is tempting to think of the “end of time” as a reference to the composer’s fear of not surviving the war, Messiaen later wrote that the piece looks beyond the temporal to “the abolition of time itself, something infinitely mysterious and incomprehensible to most of the philosophers of the time, from Plato to Bergson.”

The Quartet actually forms a natural line from the composer’s previous works (the fifth and eighth movements, for solo cello and solo violin respectively, are drawn almost verbatim from works Messiaen composed during the previous decade) and is “of a piece” with the massive works written in the years after his captivity: the Visions de l’Amen for two pianos, the Trois petites liturgies for choir and ensemble, the 75-minute Turangalîla Symphony, and the two-hour Vingt regards sur l’Enfant-Jésus for solo piano.

As to the question of how much historical information an audience needs before listening to such a work, musicians tend to be fairly open on this topic. “Every audience member is going to have a different experience,” Alex said, “and personally I always prefer to allow the audience to have the experience they want. … You provide them with the historical information, and if they’re fascinated by that, great.”

Yet a musician’s goal is to create an experience that works outside the verbal: “It’s what you create with sound, with your interpretation,” Alex said. “If you tell people going to a museum exactly what they should be experiencing, for example, it’s going to turn them off. They’ll feel constricted in their experience.”

Many first-time listeners are flabbergasted by the Quartet’s sheer complexity of ideas, and its dazzling sound-world. Learning of its origins in a prison camp — where disease, freezing temperatures, and starvation were a part of daily life — only heightens a sense of wonder at Messiaen’s achievement.

“If I composed this quartet, it was to escape from the snow, from the war, from captivity, and from myself,” the composer would write. When captured, Messiaen had retained a small satchel of miniature scores: music ranging from Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos to Alban Berg’s Lyric Suite that would be his “consolation from hunger and cold.”

French captives were generally treated more humanely than many others. Henri Akoka, the only Jew in Messiaen’s ensemble, was very nearly deported during his repatriation and later found himself escaping from a moving train “with his clarinet under his arm,” according to one account. He later remarked that the Quartet was “the only memory of the war that I wish to keep.”

The Messiaen forms the centerpiece of Summerfest’s opening weekend. Subsequent weeks will include Vaughan Williams’ rarely heard Piano Quintet in C Minor (which was withheld from the public for 80 years), Beethoven’s youthful Septet, Op. 20, Dvořák’s String Quintet in G major, Op. 77, and Jennifer Higdon’s Love Sweet, among other gems.

“It’s perseverance, and the pure love of chamber music” that has sustained Summerfest for this long, Jane said. For musicians who perform in orchestras during the year, chamber music “affords a level of intimacy in communication and decision-making that is very attractive, from a performance standpoint.”

—By Paul Horsley

Summerfest runs from July 6th through the 28th. For tickets and information, go to summerfestkc.org or call 816-895-2920. To reach Paul Horsley, performing arts editor, send an email to paul@kcindependent.com or find him on Facebook (paul.horsley.501) or Twitter/Instagram (@phorsleycritic).