For more than five centuries, European settlers went to extravagant lengths to erase Native American tradition, culture, and even language from the face of North America. The effect was devastating for Native peoples already contending with disease, massacres, and forced displacement.

The past half-century has seen a dramatic turnaround, both in attitudes and in legal protections for Native American culture. An early gesture toward this was the Native American Programs Act of 1974 (NAPA), a law promoting economic and social self-sufficiency and focused on well-being and on economic cultural development within Native communities.

This was bolstered in 1990 by the Native American Languages Act (NALA) promoting the use of, and preservation of, languages through use in public schools, linguistic research, and college curricula.

All of this came too late for many of the 300 languages that once thrived in what is now the United States. Some 120 languages remain, in one form or another, but each year several fall dormant as the last speakers die.

Though languages such as Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, and Diné (Navaho) are still spoken by thousands, there are dwindling numbers of “L1” speakers, as linguists call those for whom a language is their primary mode of communication — a mother tongue. In addition to these are “heritage speakers,” who grow up learning parts of a language from family members but for whom English is primary.

“We see this ‘heritage acquisition’ among immigrant populations as well,” said Andrew McKenzie, a University of Kansas associate professor of linguistics who specializes in Native American languages. “But there’s more of a worrisome sense about it here. Because with immigrant populations the language is fine back in the old country; with indigenous languages, this is the old country, so as the L1 speakers pass on, that knowledge passes with them.”

Linguists are finding ways to revive “lost” languages. “These languages can be brought back,” said Andrew, whose great-grandfather, Parker McKenzie, was a central force in the systematic preservation of Kiowa nearly a century ago. “With thorough documentation and enough work, we’ve seen that this can be done. So instead of talking about a language as extinct or dead, we usually describe it as dormant.”

The last L1 speaker of Kaw (Kansa), for example, died in 1982, but researchers had already preserved hundreds of hours of recorded speech from the last survivors, from which instructional manuals were prepared and are used by members of the tribe. “Enough of it was preserved and recorded that the language is being taught in the Kaw community,” Andrew said. “It can be brought back and maybe it will flourish in the future. That’s a goal for a lot of people.”

Even a purportedly “long-lost” language can be revived. In 1993, jessie little doe baird founded the Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project, which has used the 1663 Wampanoag-language Eliot Bible and other documents to reconstruct a language that died out in the 19th century.

Still, knowing a language solely from a grammatical standpoint provides only part of the picture. “A language is more than just a system that cobbles sounds together into words and phrases in ways that scientists can reverse-engineer,” Andrew said. “It’s also the stories, the people, and the community whose threads are woven with every sentence.”

As a member of the Kiowa tribe, which is now headquartered in Carnegie, Oklahoma, Andrew has found himself learning both the language and the culture of the Kiowa even as he has become a nationally renowned expert on Native languages in general.

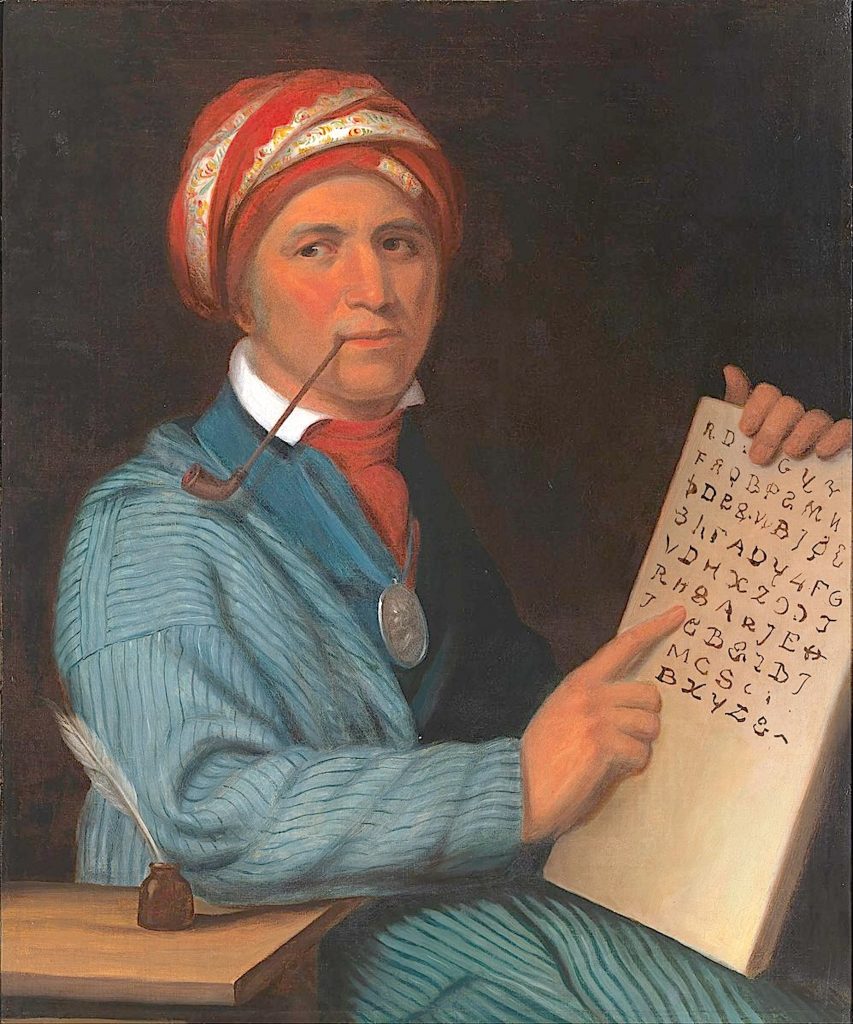

Parker McKenzie created a widely used method of writing Kiowa (his A Grammar of Kiowa, written with University of Kansas alumna Laurel Watkins, was published in 1984). But a language cannot thrive unless there is a community of Kiowa who regularly meet, interact, socialize, and tell stories.

Research is underway for other languages with ties to our region, including Chiwere, a Siouan language originally spoken by the Iowa, Otoe, and Missouria tribes. The Otoe-Missouria once occupied what is now north-central Missouri, though they were eventually driven to Nebraska and then to a reservation in Oklahoma. Thanks largely to the Otoe-Missouria storyteller Truman Washington Dailey, researchers at The University of Missouri were able to document and preserve a great quantity of Chiwere before Truman’s death in 1996.

Other languages associated with our broad region, many of whose tribes are now based elsewhere, exist in various stages of dormancy or restoration — including Kickapoo, Shawnee, Osage, Quapaw, Pawnee, Saux, Fox (Sac and Fox), Potawatomi, and Wyandot.

Today, even Rosetta Stone, the language-learning system, has an Endangered Languages Program through which it is creating materials for self-instruction in Chickasaw, Mohawk, Diné, and other Native languages.

All this is a long way from the time in which Native children were forcibly relocated to boarding schools — where they were punished, often severely, for speaking in their own tongue. An about-face was spurred by a series of programs passed into law by Congress, starting with the Native American Languages Act of 1990 and continuing with the Esther Martinez Native American Languages Preservation Act of 2006 (reauthorized in 2019), which provides immersive courses for Native youngsters and stimulates teacher training.

In 2017, First Nations — a non-profit organization created to improve Native American life through grants, training, and advocacy — established the Native Language Immersion Initiative (NLII). And in 2023, the federal office of the Administration for Native Americans invested $2.6 million to boost the vitality of native languages: an effort further energized when the U.S. Department of Education announced grants of $11 million toward bringing Native American language instruction into public schools, among other things.

Last fall, Kansas City Public Schools announced that East High School would begin offering instruction in Cherokee. “Just having classes in schools raises the profile of the language among the general public,” Andrew said.

Americans today recognize the value of language preservation and are eager to see these programs continue to grow. “Language is a core part of who we are as Indian people,” said Benny Shendo, Jr., First Nations Development Institute’s board chair and associate vice chancellor for Native American affairs at The University of Colorado-Boulder.

“Each of us has our respective languages that connect us to our place of birth, teach us how to pray, and show us who we are as Indian people. Language is sacred.”

— By Paul Horsley

____________________________________________________________________

PROF. ANDREW MCKENZIE ON NATIVE AMERICAN LIFE AND HISTORY

On correcting widely held misconceptions of Native life:

Most people don’t realize that we still exist. The story goes, “We took their land, they died, the end.” But really that phase was the beginning. Since then, Native Americans have navigated a dual world, balancing what’s best about modern life with what’s valuable from traditional ways. We seek that balance in our daily lives, in our events, in our governments, everywhere.

Also, people misunderstand indigeneity as a racial question. That is a relic of old racial ideologies that lump us all together under the “red” banner in opposition to “white” or “black” and tally up our blood quantums. But actually (and legally), our national identities are just that, and we lump ourselves together as Indians out of shared history and alliances going forward.

So a lot of folks are surprised to meet Natives who look Caucasian or African-American — because we are that too. And we always were. Intermarriage was always common, both with other tribes and with neighbors that came with the colonies. Some tribes even required you to marry outside the tribe.

On America coming clean about violence toward Native Americans through the centuries:

Well, it’s interesting because as we speak, President Biden is formally apologizing on behalf of the nation for the boarding school system inflicted on tribes. Passionately, I might add. This process clearly reflects how the history did not end with the land conquest, it only began. Yet that history is not widely known, so any step towards reversing that trend is a positive one.

Our country is slowly reckoning with this past as it inches away from supremacism generally. These steps reinforce each other. Ideally, people will know this past and wonder what the point of it all was. Not out of a sense of transferred guilt for the sins of our ancestors, but in a forward-looking determination to avoid repeating them. We can’t move on if we’re stuck in a loop. Not to mention, countless other countries have similar reckonings to make with its indigenous peoples, and the United States can show moral leadership on the issue.

On the importance of language in the reckoning process:

As a linguist, I am sensitive to another facet of this reckoning: It requires re-configuring how we talk about these historical events so we can be more honest about it. For instance, many U.S. states were built upon government redistribution of wealth: Indian lands were appropriated and then parceled out to settlers, often as free handouts, or at cut-rate auction prices. And it worked! These states prosper to this day.

We use these kinds of terms to describe other countries and political or economic systems, but we often hesitate to apply them to our own past or present. Similarly, we rarely if ever describe Jim Crow laws as tyranny, or city boss machines as autocracy, or of lynchings as terrorism, but they undoubtedly were. I think that talking about them in this light would help nudge people toward understanding what was wrong with them, so we don’t revert to it. Once was enough.

The “Indian problem” was solved by pushing Indians west until there was no more west to push them to. Then the problem was solved by forcibly assimilating them into American culture — valuing whiteness, Christianity, English language, and capitalism rooted in private property.

Kids went to schools near and far, often by force, and were drilled with military rigor for years on end to become good little farmers and housewives. As the infamous phrase went, they aimed to “kill the Indian to save the man.” The nationwide program ran in a spirit of supremacist benevolence and was the bleeding-heart solution at the time, rather than the extermination that some advocated.

This story is generally unknown: part of the general pressure to make everyone conform to the same standards. People thought they were doing the right thing, for themselves and often for the Indians too.

On creating a full image of Native history that is free of mythologizing:

A lot of people still have this idea that our lives are 100 percent different from the mainstream, when in reality, our lives are tightly integrated into modern life. Indians have always been happy to take on new technology, from firearms to kettles and wagons and horses — and nowadays from smartphones and all kinds of technology. Innovation has always been part of life for us: We keep the things that work well and replace the things that don’t. In that sense, our life is not different from anyone else’s. And we don’t all have mystical powers, either.

Sometimes it’s easy to forget that the Native people of the past were just people. They were not gods, they were not mystic beings. They were, and are, people who have principles and beliefs and sometimes base motivations. … but also practicality and ingenuity.

To reach Paul Horsley, performing arts editor, send an email to paul@kcindependent.com or find him on Facebook (paul.horsley.501) or Twitter/Instagram (@phorsleycritic).