The Lyric Opera has taken an approach to Madame Butterfly that is both graceful and honest. The production, which ran November 14th through the 16th at the Kauffman Center, treated Puccini’s controversial subject matter with subtlety and even restraint, but it did not shy away from the topics of patriarchy, imperialism, and culture-clash that make the opera’s outcome so jarring.

Based on a short story and a French novel, both partly biographical, the libretto by Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa sets up an impossible predicament which—we divine throughout—cannot possibly reach a satisfying conclusion. When Pinkerton declares, early in the opera, that despite his semi-formal marriage to Butterfly he will “someday take a real American wife,” we know that no good can come from this situation.

Having said that, the story that Puccini tells is riveting, and it contains some of his most irresistible music. No matter how many times you see this opera, the ending is a gut-punch—its impact growing largely from the way the musical drama gathers elements of fragility, danger, frustration, and passion toward its cataclysmic finale.

E. Loren Meeker’s stage direction felt natural and clear-eyed: the spare gestures gave the viewer time to reflect on the narrative and on each character’s inner turmoil. This quietness was enhanced by Christopher Oram’s muted set design, which consisted of a traditional Japanese house, lanterns and tree-silhouettes upstage, and a huge, curved ramp linking the outside world to that of Butterfly and her maid, Suzuki. The masterful lighting design of Driscoll Otto provided layered textures that enhanced the characters’ shifting emotional states. In the transitional “interlude” between Acts II and III (with the “Humming Chorus,” sung by a chorus expertly trained by Piotr Wiśniewski), we could almost feel Butterfly’s hope drain out of her, as bluish night progressed to golden daylight.

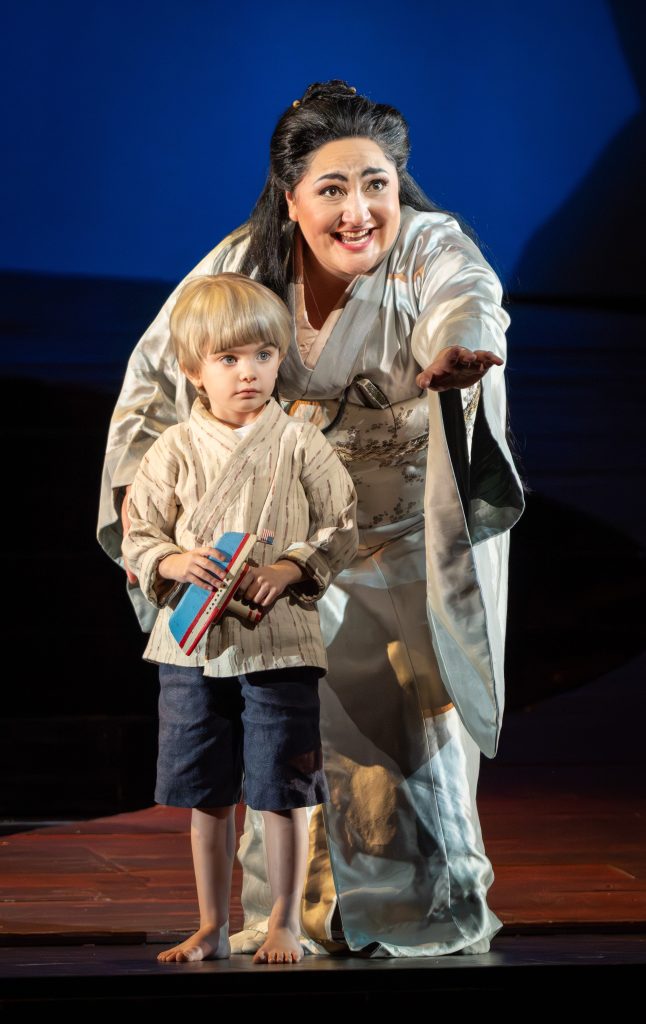

At the center of this production was soprano Yunuet Laguna’s infinitely detailed performance as Cio-Cio-San (Butterfly). With economy of movement and the most natural of facial expressions, she managed to encapsulate the whole range of emotions that a love-stricken teenager might experience—fear, resolve, naiveté, weirdness, jubilation, horror, and profound sadness. “Un bel dì” shimmered with hope and the fervor of youth, and Friday’s audience could not even wait until the end to begin its ovation.

Her voice, too, is ideally suited to this role: Rich and rounded, it glowed with energy and pathos, with colors and moods that shifted from hope to vulnerability and back again. And when, in Act III, she began to realize that Pinkerton has returned not to be her husband but instead with plans to take their son away to America, her response was so vivid that you could barely take your eyes off her. (Because the performances were on consecutive days, the Lyric double-cast the title role, with Ann Toomey singing on November 15th.)

Matthew White, whose tenor is clean and sweet-toned, sang Pinkerton with bravado and a deliberate air of detached superiority—perfectly appropriate a naval officer with a “girl in every port.” His is a somewhat lighter voice than Yunuet’s, and when they sang a due she tended to overpower him.

Yunuet’s duets with the magnificent mezzo-soprano Alice Chung (Suzuki), on the other hand, were captivating. Their voices were so neatly suited to each other—with the mature maid expressing deep concern at the girl’s infatuation—one could almost imagine Suzuki to be Butterfly’s big sister. This made for a gorgeously sync’d “Flower Duet.” Jarrod Ott was a sympathetic Sharpless (the American consul who warns Pinkerton against his folly), a role he sang with a luscious and studied baritone. Conductor Roberto Kalb led the orchestra with a feel for pacing and lush sound. Spencer Hamlin was a suitably officious Goro, Alex Smith presented a stately, rational Yamadori, and Christian Simmons sang The Bonze with solid, stolid strength.

It is atypical for an opera of this period to make the “romantic hero” into a cad (though examples do exist), and the authors of Butterfly struggled with just how unsympathetic a character Pinkerton should be. When audiences at the La Scala premiere were outraged at the “evil Pinkerton,” the authors tried to soften him around the edges—removing some of his offensive comments about Japanese culture and adding his remorseful final “Addio, fiorito asil.”

The Lyric has pushed Pinkerton to the background, choosing instead to focus on the endlessly fascinating Cio-Cio-San, who despite her youth remains true to her code of honor. Her obstinate belief that Pinkerton will return is both frustrating and admirable; her undying love for him is less about obsession, perhaps, than it is about dignity and principle.

Her piteous final sacrifice is one of the most selfless acts in all of opera. That she believes death to be her only viable option makes her fate all the more tragic. But that she sees it as a way to lift her son out of poverty makes her an almost inadvertent heroine.

—By Paul Horsley

For information about upcoming Lyric Opera productions, call 816-471-7344 or go to kcopera.org. To reach Paul Horsley, performing arts editor, send an email to paul@kcindependent.com or find him on Facebook (paul.horsley.501) or X/Instagram (@phorsleycritic).