Nathan Bowman doesn’t always advertise his Native American heritage when presenting himself to the public, but he is nonetheless proud of the deep roots that his family has always known are there. The co-founder and producing artistic director of Kansas City Public Theatre was raised knowing that, at the very least, he was descended on his mother’s side from members of the Wyandotte Nation of Kansas (separate from, but historically connected to, the Wyandotte Nation of Oklahoma).

But because his maternal grandmother was adopted by a non-Native family in a closed adoption, completing the paperwork needed to establish Wyandotte citizenship has proved difficult. “You have to trace your family lineage to the last-taken census of the tribe from the late 19th century… using genealogical documentation and birth certificates,” said Nathan, a nationally acclaimed actor, director, and playwright. “So it’s quite a long process… and obtaining a birth certificate when there is a closed adoption in the middle of it makes it difficult.”

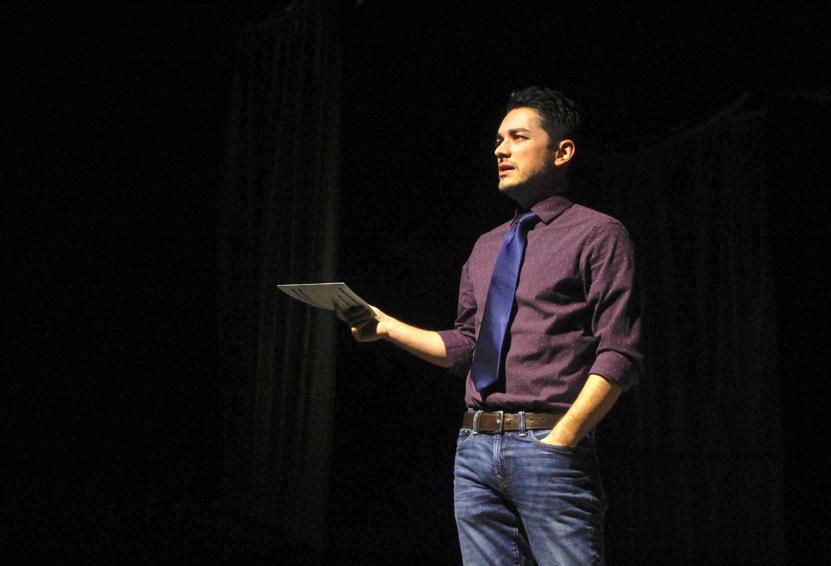

As assistant professor and chair of theater and dance at Benedictine College, Nathan Bowman teaches courses in movement, Greek tragedy, theater history, religion, directing, stagecraft, and sound.

Nathan Bowman and Elizabeth Bettendorf Bowman co-founded Kansas City Public Theatre in the 2017-2018 season.

Despite these challenges, Nathan has continued the process of making it official: Being Native American is an important part of his identity. “It seems like you always have to justify your heritage in some way when you’re Native American, because so many people claim that they are,” he said. “What you’re entering into is citizenship … which is not the same thing as whatever race or ethnicity you are.” Nathan is mistaken for Hispanic on an almost daily basis, which is fine except that he is not. “Having citizenship in a tribe is important: It’s an indicator that you are actually Native American.”

An Assistant Professor and Chair of Theatre and Dance at Benedictine College in Atchison, Kansas, Nathan co-founded the Public Theatre in 2017-2018 with his wife, Executive Artistic Director Elizabeth Bettendorf Bowman. Together they have made this company into a vital part of the Kansas City theater scene: offering free theater at a variety of offbeat venues and tackling a range of works that demonstrate diversity as a core value.

Nathan Bowman served as sort of the Greek chorus in his Faustus, an adaptation of Christopher Marlowe’s version of the centuries-old tale, and Joshua Gleeson (with back turned) play Dr. Faustus. / Photo by Micah Thompson

Nathan Bowman is the chorus and Kitty Corum is Mephistopheles in Faustus, performed by Kansas City Public Theatre in 2022. / Photo by Micah Thompson

Most powerful, perhaps, have been the deft adaptations of classics: a reflection, primarily, of Nathan’s background as an expert in the field of ancient Greek theater. It was the focus of his Ph.D., which he earned from The University of Kansas (Spectacles of Horror: Approaching the Supernatural in Greek Tragedy), and it has remained at the center of his activities. Nathan performs frequently in ancient theaters in Greece, both in English and in Greek, and his adaptations of classical drama (Medea: An American Tragedy; Oedipus the King) have formed an important part of Public Theatre’s repertoire.

All of this has relevance for Nathan’s identity as a Native American theater artist, for several reasons. First, in both ancient Greek and Native American has traditions, the line between ritual and theater always been indistinct. “What could easily be called ‘Native American theater’ was never given this distinction, because it didn’t meet the narrow definition of the ‘well-made play,’ of the Western tradition,” said Nathan, who also holds a master’s degree in religious studies. “Greek tragedy is very much like that: overtly religious and ritualistic in a way that we don’t often give it credit for.”

Second, Nathan was recently energized to create a brief adaptation from The Oresteia of Aeschylus, which he presented as a 20-minute Native American re-envisioning of this ancient tale. In his one-man version, Nathan is Orestes, the adopted patriarchal son of Clytemnestra: who has killed her husband to avenge her daughter’s death. Orestes’ subsequent act of killing his mother has sometimes been viewed as a moment of “patriarchy supplanting matriarchy,” Nathan said, “and I found in that a metaphor for colonization, to some degree.”

In April 2022, the Missouri Arts Council named Kansas City Public Theatre “Arts Organization of the Year.” Pictured are Missouri Arts Council Executive Director Michael Beshore, Nathan Bowman and Elizabeth Bettendorf Bowman, and Arts Council Board Chair Sharon Donovan. / Photo by Lloyd Grotjan

Many tribes, including the Wyandotte, are matriarchal, and the conquest of the Americas by the fiercely patriarchic European culture does indeed fit into a sort of Oresteian narrative. In this version, Nathan is Orestes, “a Native American man, who is perpetuating the primarily white American patriarchal culture, as opposed to defending his mother,” he said. The killing of Clytemnestra becomes a symbol of the storyteller’s own suppression of his Native American culture: as he embraces, instead, the new society of the European conquerors.

“It’s sort of personal: I’m writing from the perspective of my own life,” Nathan said of the retelling. “As an artist I don’t really explore Native American themes a lot, and sometimes there is a sense of guilt: that I need to be doing more of that.”

He would indeed like to produce more theater that reflects on his heritage, but as someone not raised in a tribal society, he feels a need to educate himself more thoroughly. “There is quite a long list of companies and of working Native American playwrights right now,” he said. “But if I were to continue to produce art that reflected on this, I would want to make sure it was reflective of my experience and my story. … People who do this really have to buckle down in their research and learn about their heritage.”

Featured in the November 11, 2023 issue of The Independent.

By Paul Horsley