Countertenors have been with us for hundreds of years. If it seems that they are suddenly everywhere, it’s partly because the demand for them internationally has spurred conservatories toward a new level of training, to the point where we suddenly have dozens of really great ones. It took the Metropolitan Opera National Council Auditions nearly 40 years to award one of its top prizes to a countertenor, in 1991, but since then a half-dozen more singers in this most unusual vocal range have received the prestigious distinction.

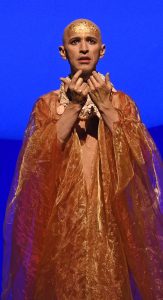

One of these, the 39-year-old Anthony Roth Costanzo, is bringing unprecedented attention to the countertenor voice through stellar successes in opera, concert, and even cabaret-style programs. Most notably, he was the star of one of the Metropolitan Opera’s runaway hits of the last decade, director Phelim McDermott’s massive production of Philip Glass’ Akhnaten, which overnight made Anthony into one of the hottest tickets in opera.

Photo by Matthew Placek

On December 18th at the Folly Theater, Anthony will become only the second countertenor to appear on Kansas City’s Harriman-Jewell Series in its entire 57-year history. And it’s no exaggeration to say that he fits perfectly into a series that has presented nearly every major operatic star of the last half-century on its stages. Anthony is, quite frankly, one of the most exciting singers you can hear today.

He and Canadian Pianist Bryan Wagorn will present an innovative mix of works by Henry Purcell, Benjamin Britten, Franz Liszt, George Gershwin, and the American composer, Joel Thompson: as well as Hector Berlioz’ complete Les nuits d’été (Summer Nights), a delicious song cycle that is traditionally sung by mezzo-sopranos.

“A recital is kind of the most intimate way to understand an artist,” Anthony said recently from Madrid, where he was preparing for a production of Handel’s Partenope.“In opera, we’re playing a character, so that’s kind of a veil, or sometimes a kind of an obstacle if you will, between the audience and the person. So the first thing I do when constructing a recital is to look at what feels like an expression of me, or of my voice.”

Anthony believes that conversation is essential to the experience. “Recitals are not just about singing, they’re also about talking: talking about the pieces, about where they fit into my life, and kind of having a relationship with the audience which is much more intimate, and much more personal.”

This May and June, Anthony will repeat his portrayal of Akhnaten in the Metropolitan Opera’s Phelim McDermott production of Philip Glass’ opera, which features sets and video designs by Tom Pye, costume designs by Kevin Pollard, and lighting design by Bruno Poet / Photo by Karen Almond

Kansas Citians are fortunate to get to know Anthony on such an intimate level, as his fame is quickly becoming outsized. Of his performance in Akhnaten, in which he plays one of ancient Egypt’s most controversial pharaohs, The New York Times declared that he “truly owns” the role, and praised his singing for its “gleaming high notes and melting sound that cut through the orchestra with surprising ease.”

“He’s a full-blown superstar, and is just enchanting to listen to,” said Clark Morris, the Harriman-Jewell Series’ executive and artistic director, who attended the Met’s Akhnaten in New York and was blown away by it. “It was completely sold out … and the place just went crazy for Anthony, the star of this modern opera. I found it to be stunningly beautiful.” (In November, Orange Mountain’s box set of the Met’s Akhnaten was nominated for a Grammy Award in the Best Opera Recording category.)

Clark Morris

Clark and his team of course already knew of Anthony’s rising fame when they booked him here: In addition to his Met win in 2009 he has received a whole succession of awards, including being named Musical America’s Vocalist of the Year.

“He’s not just an opera star,” Clark said. “He inserts himself into all kinds of interesting, creative things. He’s been on Broadway, he’s produced his own shows. … He has this incredible stage charisma … and he is the nicest, calmest, most generous human being you could imagine.”

Exactly what is a countertenor? It is essentially a male who has developed what we think of as falsetto range (often called the “head voice,” as opposed to the more commonly used “chest voice”) into something with the full bloom and power of an operatic voice.

“We tend to call men singing in their head voice ‘falsetto,’ ” Anthony said. “We don’t say that for women, although it’s really the same function and the same mechanism, it’s just that a woman’s chest voice is a little bit closer to her head voice generally. Because the chest and head voice of a male are further apart, they say it sounds ‘false’ … which is where the Italian ‘falsetto’ came from. But it’s really just employing the head voice to sing in that register.”

As the number of countertenors continues to grow worldwide, scholars have begun to notice “types” of high-male singing, according to Kansas City-based (and nationally renowned) Countertenor Jay Carter. “The term is really in need of more specific subdivisions, almost like we see in the Fach system (vocal categories),” said Jay, a William Jewell College alumnus who earned his advanced degrees from Yale University School of Music and UMKC Conservatory before joining the faculty of Westminster Choir College in Princeton, New Jersey.

Jay Carter / Paul Sirochman Photography

“We talk about a spinto soprano or a buffo bass, and we ought to think of countertenor as a general term under which there is a realm of possibilities,” he said. When Jay first began to explore his own voice, he found a dearth of contemporary research into the mechanism of the countertenor voice. So he did quite a bit of his own research, listening to numerous great countertenors on disc and discovering an enormous variety of approaches to vocal production.

He found that, roughly speaking, there are “falsettists,” whose sound is a mixture of head voice with some chest voice in the lower register, and “fuller” voices that use more chest and often approach a high-tenor sound. Often repertoire drives the type of voice called upon, Jay said, providing “a continuum of possibilities.”

As the use of countertenors becomes more widespread, especially in performance of Baroque music, audiences are becoming more accustomed to, and accepting of, this very specific sonority. “I see a decided reduction in what I used to call the ‘program flip,’ ” Jay said with a laugh. “It would usually happen early on in Messiah performances. … As soon as I open my mouth, people grab their program and start flipping through, thinking: What the heck am I hearing?”

Anthony performed the title role in the Met’s sold-out sensation of 2019, Philip Glass’ Akhnaten, which was broadcast worldwide on the Met’s Live in HD series. / Photo by Karen Almond

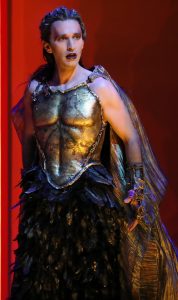

He also sang Dionysus in John Corigliano’s The Lord of Cries, a daring mashup of Bram Stoker’s Dracula and Euripides’ The Bacchae, this summer at Santa Fe Opera. / Photo by Curtis Brown.

Yet while categories can sometimes be identified, each countertenor has a distinctive sound. “Everyone has a different talent or facility,” said Anthony, who had already sung as a boy soprano on Broadway and in national tours of The Sound of Music and Falsettos when he first sang in an opera and began regarding his voice from a different standpoint.

“When I was 13, I first heard what a countertenor was, and I began to think about it.” He was performing the role of Miles in Britten’s The Turn of the Screw, and as he was surrounded by professional opera singers, some suggested that he might actually be a countertenor.

From there he began developing the voice, first at Princeton and then at the Manhattan School of Music.

But he is still grateful for his Broadway experience, which he said “instilled a kind of reverence for theater, and an understanding of theatrical instincts, which I think has served me very well in opera.”

—By Paul Horsley

For tickets to the December 18th recital, go to hjseries.org or call 816-415-5025. For more information on Anthony go to anthonyrothcostanzo.com.

To reach Paul Horsley, performing arts editor; send an email to paul@kcindependent.com or find him on Facebook or Twitter (@phorsleycritic).