Lynn Nottage’s play Clyde’s takes place in a “liminal space,” as the playwright has written, a truck-stop sandwich shop that is trying to “carve out space in a rapidly evolving landscape.” This place of transition is a bit like Lynn’s work itself: Her impressive output stands as a refreshing, transformative locus within the shifting terrain of American theater.

Lynn Nottage / Photo by Gregory Costanzo

The New York-born, two-time Pulitzer Prize winner is one of a growing number of Black women who are telling stories that have, quite simply, never been told on the American stage before.

“Thirty years ago, I looked around and found that there were very few women playwrights being published,” said Cynthia Levin, producing artistic director of the Unicorn Theatre and an advocate of Lynn’s work for two decades. “And when I looked further… I found that less than one percent of the published plays were written by women of color.”

Much has changed since Lynn’s plays began to shake up American theater in the late 1990s, even though Cynthia said that to a great extent “it is still a very white male landscape, when you look at the playwrights, the actors onstage, the character breakdown.”

Cynthia Levin / Photo by Manon Halliburton

Although Lynn and others such as Dominique Morisseau, Pearl Cleage, and Jackie Sibblies Drury have consistently been denied entrée to major stages over the years, their influence is growing, and rapidly. A recent survey in American Theater magazine found that Clyde’s, which received its Broadway premiere in November 2021, will be the most-produced play in the United States this season, with some 11 productions nationwide.

The Unicorn Theatre was one of the first to throw its hat into the ring for Clyde’s, as it has been presenting Lynn’s work since its 2001 production of Mud, River, Stone. This November 30th to December 18th, Clyde’s will be the sixth Unicorn production of a Lynn Nottage play: Damron Russel Armstrong will direct. And there is a growing consensus among theater producers that not only is this one of Lynn’s best works, but it is one of the most significant American plays of the 21st century.

Damron Russel Armstrong

“When I saw this play last January in New York, it was an inspirational moment for me,” said Cynthia, who has also presented Intimate Apparel (2007), Ruined (2011), By the Way, Meet Vera Stark (2014), and Sweat (2018). “In the last couple of years, there haven’t been a lot of exciting things that really energize you, that keep you going,” she added. “Clyde’s did that for me. It was just as exciting as heck. … It was one of those moments of, Oh my gosh, this is why I do what I do.”

Clyde’s is not just any diner: It is a last-chance place of employment for recently incarcerated men and women from a wide range of backgrounds. At the center is Clyde, a tough woman in her 40s who is “fierce and sexy,” in Lynn’s description, “all steel, unmovable. … The gravel in her voice betrays a life of cigarettes and whiskey, lived with gusto and no apology.”

Clyde (played here by Kansas City stage veteran Cecilia Ananya) is most likely an ex-convict herself, and she tries to balance a guarded empathy with an overly assertive control over her unruly staff. “Control is very important to her,” said Cecilia. “That rigidness she has is, I think, a space to keep herself safe, to try to keep from recidivating herself back into the prison system.”

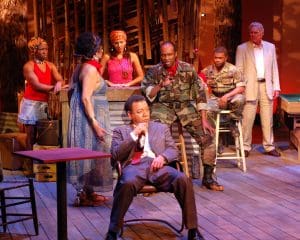

Walter Coppage was flanked by Chioma Anyanwu, Nedra Dixon, Caroline Gombé, Damron Russel Armstrong, John L. Lewis IV, and John Rensenhouse, in the Unicorn Theatre’s 2011 production of Ruined, the play that won Lynn Nottage her first Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 2009.

Of nearly equal importance is Montrellous or Monty (played by L. Roi Hawkins), a meticulous would-be chef for whom the making of sandwiches is a zen-like experience. In comes Letitia or Tish (Jenise Cook), who robbed a pharmacy to get meds for her child but “took me some oxy and addy to sell on the side,” Rafael (Freddy Acevedo), who held up a bank with a BB gun, and Jason (Zach Sudbury), who comes complete with white supremacist tattoos on his face.

Throughout the dull routine of making grilled cheese sandwiches for truckers all day, each of the characters fantasizes about his or her ideal sandwich. “Maine lobster, potato roll gently toasted and buttered with roasted garlic,” says Monty, “paprika, and cracked pepper with truffle mayo, caramelized fennel and a sprinkle of… of… dill.” As in the Unicorn’s 2017 production of Will Snider’s How to Use a Knife, this virtuoso production will feature a fully functioning kitchen. “We will be cooking,” Cynthia said. “We will be making the sandwiches onstage.”

Justin Speer, Donette Coleman, Dianne Yvette, Katie Karel, and Marc Liby starred in Lynn Nottage’s By the Way, Meet Vera Stark, a witty critique of old Hollywood’s racial stereotypes that the Unicorn brought to the stage in 2014.

If Clyde’s feels like a moment of sudden arrival for Lynn, it is not. Her successes (including Pulitzer Prizes for Ruined and Sweat) have come after decades of struggling to be heard. “Making theater is very difficult,” Lynn recently told Essence magazine. “Making theater when you’re a Black woman is doubly difficult.”

Early in her career she was often told by managers and artistic directors “that they, meaning white people, needed some way to access this work,” she said. Which was code for: place a white character at the center.” This and other indignities have been a way of life for Lynn and others.

And this is precisely why works such as Clyde’s are so important. “Because of Lynn’s consistent writing, and her incredibly wonderful writing… she got to be known, and finally she has come into her own,” Cynthia said. “But there are other writers out there.” American theater has for two centuries dwelled almost entirely on the problems of middle-class white families. “We can no longer be blind to the fact that there are other voices out there that must be heard.”

—By Paul Horsley

For tickets, call 816-531-7529 or go to unicorntheatre.org. To reach Paul Horsley, performing arts editor, send an email to paul@kcindependent.com or find him on Facebook (paul.horsley.501) or Twitter/Instagram (@phorsleycritic).