In the mid 1800s, many who were enslaved traveled through Missouri to Kansas, seeking to escape the bonds of slavery. While Kansas Citians know of Quindaro Boulevard, its namesake was an early Kansas settlement that was integral to the pre-Civil War abolitionist movement. Known today as the Quindaro Ruins, the area is significant to Black history as well as to the Wyandot Nation, who settled the townsite. While time seems to have forgotten old Quindaro, its future prospects of renewed recognition have suddenly become brighter.

Founded in 1854, Quindaro was a Missouri River boomtown. It was named after Nancy Brown Guthrie. Her native name, Quindaro, translates to “bundle of sticks,” signifying strength in numbers. The name proved meaningful, as the Wyandot Nation of Kansas effectively leveraged the strength of their community to aid in a resistance against pro-slavery laws. Originally hailing from Ohio, the Wyandot were abolitionists who had previously established an Ohio stop along the Underground Railroad – a series of safe houses in which enslaved people found passage to free states.

Chief Judith ‘Trǫnyaęk’ Manthe, of the Wyandot Nation of Kansas, is a descendent of the Quindaro settlers. “There was a longstanding tradition of the Wyandot to protect escaped slaves,” she said. “We felt they were people of the land, just as we were.” With these values, Quindaro was established as a free-settlement port along the Missouri River. According to Chief Judith, the town prospered due to its location along the waterway, with as many as 36 steamboats docking in a single day. “It had the best natural rock ledge for the steamboats to dock, so traffic was heavy,” Chief Judith said. “It was quite the town for a new settlement with a schoolhouse, a church, 16 business houses, and 30 to 40 homes.”

Chief Judith ‘Trǫnyaęk’ Manthe, of the Wyandot Nation of Kansas, is a descendent of the Quindaro settlers. “There was a longstanding tradition of the Wyandot to protect escaped slaves,” she said. “We felt they were people of the land, just as we were.” With these values, Quindaro was established as a free-settlement port along the Missouri River. According to Chief Judith, the town prospered due to its location along the waterway, with as many as 36 steamboats docking in a single day. “It had the best natural rock ledge for the steamboats to dock, so traffic was heavy,” Chief Judith said. “It was quite the town for a new settlement with a schoolhouse, a church, 16 business houses, and 30 to 40 homes.”

The bustling town was home to a variety of trades businesses, from a stoneyard and carpenter shop, to surveyors, cabinet makers, blacksmiths, and more. Additionally, the town had hotels, including the Quindaro House, owned by Chief Judith’s great-great-grandfather, Ebenezer O. Zane. Incidentally, the hotel housed a secret passageway to usher escaped slaves to safety. “It was the second largest hotel in the territory,” said Chief Judith. “He had a tunnel going from the river to his house for slaves to come in and to get them to protection.”

Another known safe house in Quindaro was called “Uncle Tom’s Cabin”, by the residents, which Chief Judith noted was discovered during an archaeological survey. According to her, Quindaro’s position, perched on a bluff above the Missouri River, provided an especially helpful vantage point. It allowed the Natives to spot escaped slaves seeking safe haven, as well as to detect slave hunters and warn freedom seekers to take cover.

Besides the bluffs, Quindaro’s port played an important role in aiding escaped slaves. The Missouri River was a barrier between slavery in Missouri and freedom in Kansas. Abolitionists in Parkville, Missouri, were known to ferry freedom seekers to Quindaro. From Quindaro, many escaped slaves would be guided to Lawrence and ushered through nearby Underground Railroad stations along the way. Some of these included Leavenworth and Atchison, both located in Kansas. “We were very, very careful,” Chief Judith said. “There was only one slave that was ever captured that we had tried to get to safety. The rest of them made it to safety.”

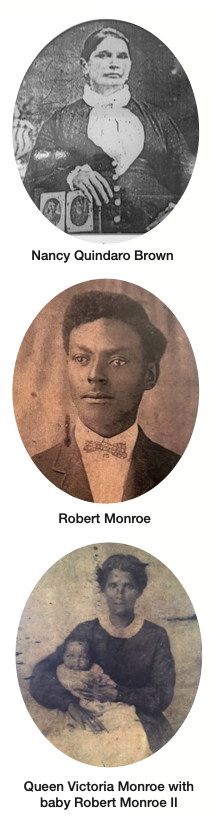

Today, nine direct descendants of Quindaro’s freedom seekers remain in the area, said Chief Judith. Anthony Hope is one such area resident. His great-great-grandfather, Robert Monroe, had been a slave in Clay County, Missouri, working on a tobacco farm. “In 1856, during a winter like this, the river froze over, and he brought the family here across the ice to Quindaro,” Anthony said. “The Wyandot were already here, and they adopted my family and we lived with them. To this day, we’re still in contact with the Wyandot Nation.” Currently, Robert Monroe’s descendants live a stone’s throw from the original townsite. Anthony’s home is a few blocks away, and his mom, aunt, and extended family also reside nearby.

Unfortunately, since Quindaro’s historic boomtown days, the townsite has fallen to ruins. During the Civil War, it was abandoned and marauded. “There are no buildings down there – just rock foundations,” said Chief Judith. “The Civil War is what actually destroyed Quindaro. The United States Army moved in, and they used all of the boards off of the houses for firewood. They were using my second great-grandfather’s hotel as a stable for horses and everything was just torn up.”

As time wore on, the significance of the ruins went unnoticed. According to Anthony, in the 1970s there was talk of turning the ruins into a landfill. He and other locals formed a group called The Concerned Citizens for Old Quindaro. “We made them (the city and the church which owns the land) do an archeological study,” he said. “They had people come in from National Geographic and Kansas State University.” The study revealed the foundations of the 1850’s townsite, which Anthony said was dubbed the Pompeii of Kansas. As a result of these findings, the area was preserved. In 2002, it was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

Regardless, the ruins of the historic townsite have languished due to lack of funding. However, in December 2023, Governor Laura Kelly granted Quindaro one million dollars. Chief Judith said the initial vision is to transform the area into a tourist destination with trails, interactive educational features, and a museum. “More money to help with trails and to clean up the area would really bring a lot of interested people to visit,” she said. “There’s so much history right in that little area.”

For example, one feature of the ruins worth noting is the former brewery. It once had a cave-like vault where large blocks of ice that had been cut from the river in the winter were stored. “There is a hatch, or an opening, that you can actually walk into and see where slaves would go and drop behind the ice to hide,” Chief Judith said. “Important little spots like this need to be preserved.”

The ruins aren’t the only features in need of preservation. Historic buildings and grounds also require attention. One such spot is the John Walker Home, which houses The Old Quindaro Museum and Information Center. The historic home was owned by the son of a former Mississippi slave, John Walker, Sr., who found freedom in Quindaro. As Anthony tells it, John Walker, Sr. set up a successful shoemaking shop in Quindaro and was found dead inside of his business, due to apparent foul play. Later, John Walker, Jr. became well-known as a postman and the caretaker of Western University College. As the groundskeeper, he raised enough money to import a statue from Italy of the abolitionist, John Brown. The statue stands today on the long-closed campus of Western University which opened in 1865 and closed in 1943.

Anthony now oversees the John Walker house museum and is working to raise funds to repair the roof, stabilize the structure, and reopen the attraction. Reflecting on the significance of old Quindaro, Anthony expressed how meaningful it is to be able to trace family roots and to know and understand family history. “We’re trying to preserve our history for our youth and some of the people who don’t know about Quindaro,” he said. “We’re trying to preserve the knowledge of slavery, Quindaro, and the area of Wyandot County.”

Like Anthony, Chief Judith is passionate about preserving the area’s history, beyond the oral traditions of local families who have kept its memory alive. Her hope is that by preserving Quindaro, its history will never be forgotten nor repeated. “As time goes by, old memories and stories get diluted and lost with time,” she said. “You’ve got to remember that history. You can’t destroy it.”

Featured in the February 10, 2024 issue of The Independent.

By Monica V. Reynolds