Paul Gardner is shown beside the 18th century “Portrait of a Girl” by Giovanni Battista Piazzetta, a gift to the Nelson Gallery by Mrs. Edwin W. Shields, in recognition of his directorship of the gallery since the day of its opening in December, 1933. Reprinted from the April 4, 1953 issue of The Independent.

Paul Gardner arrived in Our Town early in 1932. At that time, he was the assistant to the Trustees of the William Rockhill Nelson Trust. Paul took up residence at the Sophian Plaza, across the street from the site where the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery of Art and Mary Atkins Museum of Fine Arts (later The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art) was under construction. Paul was actively involved in the layout of the Museum’s interior spaces. As Kristie C. Wolferman notes in The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A History, “He made decisions on wall coverings, seating arrangements, and the size of rooms… he saw each gallery as a stage set and tried to make each vista beautiful.” His work was all-encompassing: it included hiring staff members, arranging to borrow art for the opening, designing benches, and overseeing innumerable other details. From the beginning, the Nelson benefited from his influence.

Paul quickly met with favor in Our Town. A Kansas City Star reporter was impressed by a lecture Paul gave to the Women’s Chamber of Commerce in March 1932: “Dr. Paul Gardner brought even the artists back to life for a moment, so intimately did he attach their characters to their pictures… He speaks not purely as a technician of art or as a biographer of artists, but blends the two… Those who heard Dr. Gardner will be able to view the Nelson collection with a sympathy not possible to one with no understanding of the men who painted the pictures, and the eras in which they painted.” Newspaper readers might have envisioned a venerable art history professor. Paul was not yet 40 – and his life story was anything but dry and academic.

Paul was born in Boston, Massachusetts, in 1894. He studied at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in order to become an architect, but World War I changed his plans. Paul served in the United States Army Coast Artillery Corps, where he attained the rank of captain. His military service took him to France, and he earned the Croix de Guerre with palm. At the end of the war, Paul spent time traveling in Europe and studying art, a practice he continued during the summers for the next decade.

His next occupation, however, was unrelated to architecture: he became a ballet dancer, using the stage name Paul Tchernikoff. He also earned a master’s degree in European history from George Washington University. In 1930, he began taking classes at the Fogg Art Museum at Harvard University with an eye to a future career. For most people at the start of the Great Depression, this wouldn’t have been an option. Others would have had to retrench, settling for work outside their field of study. For Paul, it was exactly the preparation he needed.

In September 1933, Paul officially became the director of the gallery. When the opening was held that December, he received a considerable amount of praise. One after-dinner speaker, quoted in the Kansas City Times, stated, “You can’t hang a gallery with a step ladder and a few nails, and I should say that the power of the gallery is in the masterly manner in which the director, Paul Gardner, has presented his exhibits.” Another Times article noted, “Gardner, too, was responsible for an innovation in the display of small objects of art such as jewelry, vases, carvings and pottery. Their display rooms, free from showcases and glassy cabinets, seemed to have borrowed from the aquarium the devices of brilliantly lighted recesses in the walls of otherwise unlighted rooms.” In this way, Paul helped visitors see the artwork, without the distraction of elaborate containers. He also wanted them to understand what they were seeing. To that end, Paul gave a staggering number of lectures during the Museum’s early years. In March 1934 alone, his topics included French, Spanish, and English paintings in the collection; American art of the 18th century, American decorative arts (including silver and glassware) of the 18th century, Italian, Flemish, and Dutch paintings in the collection; the Impressionists, English paintings, and Oriental art. He was a very visible presence in the community. The newspapers wrote about these events, which both publicized the Nelson and brought newcomers to the Museum. For many years, he gave lectures on Wednesday evenings.

When the United States entered World War II, Paul was already well into his forties. Given his age, his military service during World War I, and his position at the Nelson, it might have been expected that he would be staying in Kansas City. That didn’t happen. Instead, Paul took a leave of absence from the Museum beginning in 1942. During his time away, he served as military governor of Ischia, an island in the Gulf of Naples, in addition to being one of the now-famous Monuments Men. In October 1943, an editorial headlined “Paul Gardner in Naples” appeared in the Times, with an explanation of his new role: “The appointment of Maj. Paul Gardner as custodian of antiquities and works of art in the Naples area constitutes a signal recognition of the standing which the director of the William Rockhill Nelson Gallery has achieved among his professional associates. Italy is one vast treasure house of the art of ancient and modern times. And not the least of the problems confronting the Allied military government there will be the protection of its monuments, churches and museums.” His work included removing artwork from areas where it might be endangered by shelling and/or harsh weather conditions. At least two other men with ties to the Nelson served as Monuments Men: Laurence Sickman, who previously had served as curator of Oriental art and who would resume his career at the Museum after the war, ultimately succeeding Paul as director, and a very young James A. Reeds II, who would become a professor at the University of Missouri-Kansas City and a docent at the Museum.

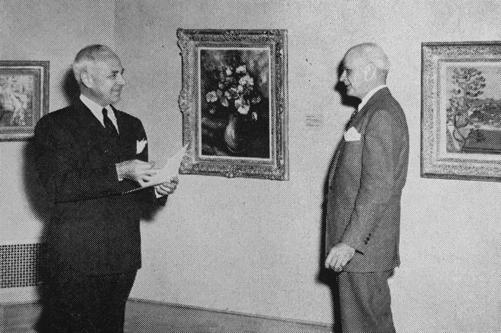

Paul Gardner, director of the Nelson Gallery, and David Mackie, chairman of the selections committee of the Friends of Art, in front of Vlaminck’s “Flower Piece.” Reprinted from the December 8, 1951 issue of The Independent.

Paul Gardner (left) Gallery director, aids James Roth (center) Gallery restorer, and George Herrick, Gallery assistant, in moving a Pergemean torso. Reprinted from the April 2, 1949 issue of The Independent.

During the war years, Paul was promoted to lieutenant colonel in the United States Army. When he returned from Europe, arriving at Union Station late one December evening in 1945, a Times reporter was on hand to record his comments. After acknowledging that he hoped to be back in his office the next day, Paul’s thoughts turned to recent events: “‘The world of European art is still a jumble,’ he said. ‘It will take some time to straighten things out. But we are gratified in our belief that comparatively little of it will be lost because of the war.’”

Paul resumed his duties, and audiences once again enjoyed his lectures. The postwar years were a busy time for the Museum. Among the highlights was the acquisition of Caravaggio’s Saint John the Baptist and the completion of the first floor, including the Gothic cloister. Paul retired in 1953, moving to the Land of Enchantment and spending summers abroad. As our scribe noted, “At his New Mexico ranch, ‘Las Milpas’ at San Patricio, he tended a precisely-rowed vegetable garden and a small orchard – his bright red apples went to friends around the country. It was here that he enjoyed the company of art greats, such as the Peter Hurds. He sold Las Milpas and settled in Lincoln, New Mexico, where a small gallery needed his help, and he spent his last years there in the open western country.” Paul died in September 1972.

For further reading:

- Churchman, Michael and Scott Erbes. High Ideals and Aspirations: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art 1933-1993. Kansas City, Missouri: The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, 1993.

- Nicholas, Lynn H. The Rape of Europa: The Fate of Europe’s Treasures in the Third Reich and the Second World War. New York: Vintage Books, 1995.

- Wolferman, Kristie C. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: Culture Comes to Kansas City. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press, 1993.

- Wolferman, Kristie C. The Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art: A History. Columbia, Missouri: University of Missouri Press, 2020.

- monumentsmenfoundation.org

Also featured in the September 19, 2020 issue of The Independent

By Heather N. Paxton