A 1937 ad for Stine & McClure (yes, the undertakers – nostalgia sells) perhaps said it best:

“No one who ever rode

on the ‘loop-the-loop’ will ever forget

the glamour of old Electric Park

at Guinotte and Agnes Avenues.

Built by the Heim Brothers in 1899

to obtain passengers for the trolley line

which had in turn been built

to carry passengers to the Heim Brewery,

it was a success from the start and

an outstanding amusement park of the west.

Electric Park was moved to

Forty-fifth and Paseo in 1907

and continued in popularity for many years.”

There were three Heim brothers. Joseph J. Heim was the oldest. Ferdinand Heim, Jr., was born in 1862, followed by Michael G. Heim. They came to Kansas City from St. Louis with their parents, Eliza and Ferdinand Heim, Sr. Their father, who was originally from Austria, was a brewer. Eliza died in 1893, and Ferd, Sr., died in 1895. All three brothers would be involved in Heim Brewery, and they would operate many other businesses together. About money, Mike was known to say, “Well, Joe makes it, Ferd saves it – and I spend it!” He was lucky to have such supportive partners, but it must be said that he came up with some grand ideas. Mike was the brother to whom Electric Park was most dear. Visitors to the original Electric Park, which was located in the East Bottoms close to the brewery, could enjoy the beer garden, modeled on those in Europe. Band concerts were a big draw, in addition to the roller coaster. There was a large illuminated fountain, where young women posed beneath brightly colored lights. As with any situation where copious quantities of alcohol are available, there was a certain amount of chaos: in 1904, Ferd Heim was stabbed by a drunken Electric Park employee at the brewery. Mike also suffered a minor wound, as he and Joe tried to wrest the knife from the assailant. Ferd recovered. Years later, it was written that Mike had anticipated the coming of Prohibition. If that’s true, perhaps it was due to this type of unfortunate event.

There were three Heim brothers. Joseph J. Heim was the oldest. Ferdinand Heim, Jr., was born in 1862, followed by Michael G. Heim. They came to Kansas City from St. Louis with their parents, Eliza and Ferdinand Heim, Sr. Their father, who was originally from Austria, was a brewer. Eliza died in 1893, and Ferd, Sr., died in 1895. All three brothers would be involved in Heim Brewery, and they would operate many other businesses together. About money, Mike was known to say, “Well, Joe makes it, Ferd saves it – and I spend it!” He was lucky to have such supportive partners, but it must be said that he came up with some grand ideas. Mike was the brother to whom Electric Park was most dear. Visitors to the original Electric Park, which was located in the East Bottoms close to the brewery, could enjoy the beer garden, modeled on those in Europe. Band concerts were a big draw, in addition to the roller coaster. There was a large illuminated fountain, where young women posed beneath brightly colored lights. As with any situation where copious quantities of alcohol are available, there was a certain amount of chaos: in 1904, Ferd Heim was stabbed by a drunken Electric Park employee at the brewery. Mike also suffered a minor wound, as he and Joe tried to wrest the knife from the assailant. Ferd recovered. Years later, it was written that Mike had anticipated the coming of Prohibition. If that’s true, perhaps it was due to this type of unfortunate event.

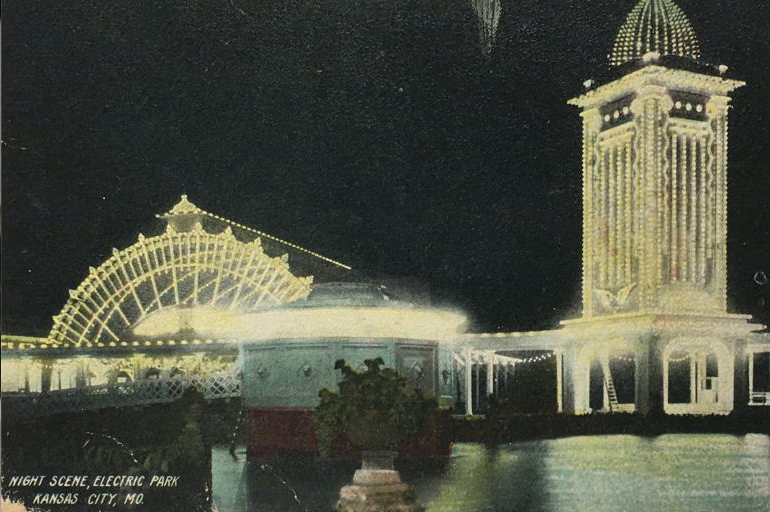

George Kessler, to whom much credit goes for the parks and boulevards in Our Town, was the landscape architect for the new Electric Park, with J.H. Martling designing the buildings. The site was estimated at nearly 29 acres (more than twice the size of the original), including a lake that covered four acres, a roller coaster, and a scenic railway. Looming above it all were two towers.

The parcel of land had previously been the home of the Kansas City Driving Club. (That was a misnomer – the members had raced horses, not cars, there.) Mike would live in the old clubhouse for many years. From an enclosed porch, he could look out at the amusement park. He spent winters in Florida, and traveled to New York to book acts.

Opening day was May 19, 1907. A crowd of 53,000 people attended, many of them arriving by streetcar. The Heims hadn’t expected any difficulty about getting a liquor license – and then hadn’t been successful. As the Star noted, decades later, “For seventeen years Electric Park was the elite amusement center of the city, and not a drop of beer was sold there.” Even when the venture proved profitable, Mike insisted on charging a penny for every glass of water, at a time when that raised eyebrows.

Writing in The Independent a few days after the opening, our scribe noted, “The covered promenade stretching its light-gemmed length around the park, and ending in huge towers blazing with lights against the sky, is most impressive. It is not difficult to believe that there are 100,000 electric lights in the park.” Among the attractions were a casino, boating, a scenic railway, and a natatorium. (That’s a swell term for a swimming pool, don’t you think?) The rides included a dip coaster, a giant swing, and a slide. The fountain came from the original Electric Park. The music pavilion seated 10,000 people. Vaudeville shows and band concerts were important to audience members, who also were thrilled by the sight of fireworks. Of it all, our scribe appears to have been most smitten by the alligator farm: “[they range] from enormous fellows as big as the one who swallowed the clock in ‘Peter Pan’ to little ones that couldn’t swallow the smallest size watch.” Sea turtles were also on display at the alligator farm, which was decorated with pineapple and banana plants, lemon and orange trees, and large palms from Florida.

The projects just kept growing. A want ad in April 1909 sought “150 Ballet Girls” to appear in a production the following year. In 1911, the boats were removed from the lake, and a beach was created there.

A Star reporter, who traveled by airplane and balloon in 1912, described how it looked from the air:

“Away over east of us lay Kansas City, a bed of twinkling lights – with the towers of Electric Park glowing like a pair of big lightning bugs that kept shining all the time, instead of turning off their lights as soon as they turned them on.”

Decades later, Henry Van Brunt, who wrote for the Star, would recall:

“Among the images… is the tap-tap-tapping of M.G. (Mike) Heim’s cane signaling a resetting of the tableau of girl models as the lights of the fountain shifted… Along with the tapping comes the smell of hot popcorn, the sing-song of barkers, the clatter and roar of the Greyhound coaster, and then – a more direct association – the fragrance of tanbark under your feet in the pavilion which John Philip Sousa once called the finest band shell in the world.”

A fire in May 1925 put an end to the glory days of Electric Park. The swimming pool and the dance hall remained unscathed, but much of the rest was destroyed. The amusement park opened for a final season that June. When it closed at the end of August, Mike said that he had missed only 13 evenings at Electric Park in 27 years.

The Heim brothers were no longer young men. Joe Heim died in 1927. After Mike retired, he spent much of his time in Florida until his death at the age of 68 in January 1934. Later that year, two men who had worked closely with him, Gabe Kaufman and Fred Spear, tried to revive Electric Park, but it was open only a short time prior to a fire that did significant damage.

The 1940s saw the death of the last Heim brother and the end of the relics of Electric Park. Ferd died in September 1943 at the age of 80. Edward R. Schauffler, writing in the Kansas City Times in 1945, noted that “the old park rounds out its existence as a golf driving range and a playground for rabbits.” Mike Heim’s former home was described as “the tumbledown clubhouse” with “empty windows.” There was some thought that the land would make a good spot for a stadium or recreation area, but nothing came of it. In 1948, it was announced that Village Green, an apartment complex, would be built on the site that had been home first to the Kansas City Driving Club and then to Electric Park.

The second incarnation of Electric Park provided fond memories for many people. Walt Disney, (perhaps you’ve heard of him?), would draw upon his recollections of it when he built his own amusement park, Disneyland, which opened in Anaheim, California, in 1955.

Also featured in the November 14, 2020 issue of The Independent

By Heather N. Paxton