‘NINE,’ MEIN HERR: Classical giants dish out Germans, Austrians and a buffet of others

By Paul Horsley

Within the space of a month, from January 16th through February 15th of this year, no fewer than nine major classical instrumentalists performed in Kansas City: violinists Pinchas Zukerman, Gil Shaham and Nicola Benedetti, pianists Garrick Ohlsson, Leon Fleisher, Jean-Yves Thibaudet and Luis Fernando Pérez, cellist Colin Carr, and percussionist Martin Grubinger. The four programs I attended, three of which are reviewed below, stood out for one reason or another. Each featured outstanding performances of standards from the 18th- and 19th-century repertoire, mostly Germanic, and three of the four highlighted Bach – almost as if it were a centenary year or something, though for the most part the alignment was coincidental.

—–

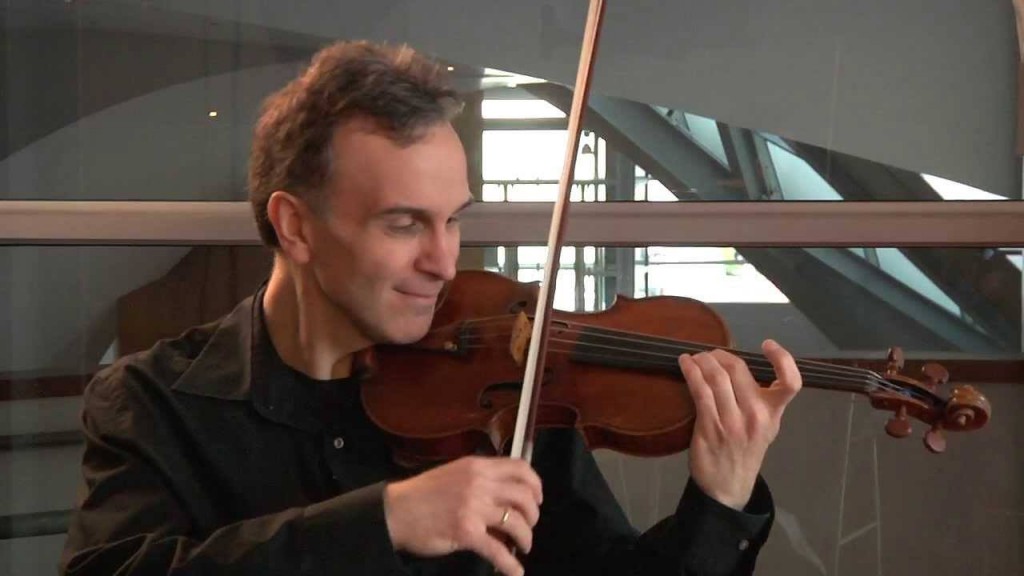

Violinist explores Bolcom’s heart, Bach’s soul

Gil Shaham’s rendering of three of the six Bach Sonatas and Partitas for solo violin – along with a work by American composer William Bolcom written partly to be played with the Bach – was a bit of an “event” even by the Harriman-Jewell Series’ high standards of star presentations. It was surprisingly well attended, too, considering it took place on February 5th, a weeknight in which snow had nearly paralyzed the city. Gil has been playing Bach’s sphinx-like works since he was a youth, as part of his education, but only recently began to play them publicly. One can see why: Even though Gil is one of my favorite violinists, in this program one had a sense he was still “finding his way” into these works.

That he can play them with utmost skill and musicality is beyond doubt. For the most part he makes them sound easy, and that’s no small task when you’re the only person onstage. How odd it is to see a trim, quizzical fellow walk onto an otherwise empty Folly Theater stage with nothing but his Strad. It’s all up to him. (“Now you know how we feel!” you hear pianists saying, with no little satisfaction.)

The A-minor Sonata began hesitantly, as if by design, with the beat of the Grave movement seeming elusive, its harmonic substance remote and strange. The subsequent Fuga sounded thorny and difficult, which of course it is. Laying bare the sense of sheer struggle (including that to stay in tune) is perhaps part of the virtue of performing these works. Gil stepped forward for the Andante, literally, making you aware of just how lonely it was up there – that a single step could have such a startling effect.

One was continually aware of the resolute yet tender attack of the beginning of each phrase, as well as the substantial new meaning given each repetition. For the Allegro he raced with effortless grace, “terracing” the dynamics from forte to pianissimo and drawing you in with the sense of line.

The shadings of phrase in the opening Allemande of the D-minor Partita might have felt a tad overwrought, but the tension of walking the fine line between passion and discipline was palpable and interesting. The Courante, at once playful and dead-serious, found Gil not so much feeling his way as exploring, pondering. (“What is this music about?”). The easeful Sarabande was balanced with a curiously playful Gigue. The Chaconne began with the “theme” stated directly and with celerity, unfussily and played more quickly than usual. Technically Gil felt in command of the variations throughout, with some tuning issues, though by the end it felt as if he was ready for it to be over.

The second half opened with the inventive, playful Suite No. 2 for Solo Violin by heroic septuagenarian American composer William Bolcom. The nine-movement structure traverses a wide range not just of emotional terrain but of violin technique. The opening “Morning Music” employs whistling harmonics and glissandi toward a humorous end, while “Dancing in Place” has the violinist creating tones by striking the strings with fingertips, in dance-like rhythmic patterns. “Northern Nigun” joins soulful melodies with a cheeky, almost mocking lilt. “Lenny in Spats” is a brief alternation of harmonics and full-bodied tone. The dance continues with the “Tempo di Gavotte Baroque” and “Barcarolle,” the latter with its passage of sustained long-note “drones” accompanied by plucked notes above. The “Fuga Melanconica” is just that, wry in its evocation of Bachian tristesse but with a wink and a nod. The frantic perpertuum mobile “Tarantella” gives way to a warm “Evening Music” that ties a bow on top.

Bach’s E-major Partita closed the program, its Preludio combining fluidity with resolute clarity. The Loure was light and airy, while the Gavotte en Rondeau explored darker, more elusive terrain. The Menuetto with its Double and the Bourrée averted a sense of courtliness with a series of playful fluctuations. The Gigue was fun and playful, with an intensity that conveyed both tension and joy.

—–

Pianist not even afraid of big, bad, late Beethoven

Garrick Ohlsson has never been one to shy from a challenge. When the towering defensive tackle of a pianist decided he’d conclude his Friends of Chamber Music program (January 31st at the Folly Theater) with Chopin’s “meaty” B-minor Sonata, he didn’t fill the first half with flashy ditties. In fact the whole program, which opened with Beethoven’s Op. 109 and Schubert’s “Wanderer” Fantasy, could have been turned upside down. “In 37 years of presenting concerts, I’ve never had anyone begin a program with a late Beethoven sonata,” said Friends founding director Cynthia Siebert from the stage before the recital. But she pointed out, savvily, the connections one might find between the Beethoven and the Schubert; with the two pieces (separated by just a couple of years) “rightfully placed next to one another” we had a chance to hear how much Schubert owed to his elder near-contemporary.

One almost wished Garrick had closed with the Beethoven, because it was so sublime that just about everything that came afterward seemed anticlimactic. The opening movement, a complex, almost improvisational piece from Beethoven’s ripest maturity, might have seemed a bit elusive – dry pedal-wise and with pensive hesitations. But one was struck by the sheer sagacity, the sense of quiet urgency that lulled you into reflection then burst into action with the Vivace. The theme for the variations was the epitome of heavenly, restful wisdom: “There’s no rush, just enjoy, let’s sit back and see what this is about.” The quicker variations displayed just enough whimsy to balance the serenity, while the slow ones, especially the finale, contained something of the ethereal bloom of the old-style German pianists such as Backhaus and Kempff.

Some of the same serenity bled into the Schubert Fantasy, where in my view it felt less welcome. The opening Allegro was less “con fuoco” than it was “ma non troppo,” relaxed and casual instead of resolute. The Adagio was sweet and sensitive but about as slow as I’ve ever heard it, straying at times dangerously close to the “precious.” The Presto sounded more natural but still too slow and hesitant; finally in the Allegro fugue we felt the rays of Garrick’s sunny personality begin to beam forth.

The second half opened with a welcome rendition of three pieces by American “Impressionist” Charles Griffes, beautifully crafted pieces that used to be more commonly heard than they are today. There’s certainly something of Ravel and Debussy and perhaps even Liszt in the lovely “Fountain of the Aqua Paola” (are all “fountain” pieces, ultimately, alike?), and the virtuosic Scherzo made a forceful impression even if it doesn’t add up to much as a piece. Not so the marvelous “White Peacock” with its quirky Debussian opening and its sensuous surface texture: beauty divorced from emotion, as with the best of the Impressionists.

Garrick is known the world over for his Chopin – early in his career he became the first American to win the Chopin International Piano Competition in Poland – and his B-minor Sonata did not disappoint. Heavy on the pedal at the opening, the Allegro maestoso noodled into comfortable places; it felt “natural,” like a piece fully integrated into the pianist’s DNA. It was played rather quietly, though, and one yearned at times for a bigger fortissimo, even if it might have exceeded the sound of Chopin’s piano. The fleeting Scherzo felt a bit “tossed off” for my taste, though this may indeed be what the composer wanted for this enigmatic interlude. The Largo let the mind wander, but into pleasant terrain. The finale, beginning from an inchoate void, built to the famous cascades that, again, eschewed the showy in search of something more meaningful. The single encore was the C-sharp-minor Waltz (Op. 64, No. 2), played with introspective hesitations and a commitment to sweet inner voices.

—–

Royal Philharmonic ‘ft. Pinchas Zukerman’ as they say in hip-hop

Pinchas Zukerman is not primarily a conductor, but orchestra musicians seem to love playing for him so much that he has eased into the role of leader with considerable comfort. He is one of the great violinists of his generation, of course, and one can easily understand how musicians in his category, after long careers of playing the same pieces over and over, yearn to mount the podium. Pinchas has made a smart career as principal guest conductor of the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra – his innate musicianship translates neatly into the role of conductor, at least with this ensemble – and their Harriman-Jewell Series appearance on January 16th at Helzberg Hall was on the whole quite satisfying.

Despite a lumbering Marriage of Figaro Overture, which was beat in “4” and sounded as if it had been set on autopilot, the two Bach concertos were an unexpected treat. (Unexpected because, due to airline delays, the whole orchestra was not available in time to perform the program as announced, which initially was to include only one Bach concerto.) Pinchas’ vigor in the A-minor Concerto’s opening movement bordered on the kick-ass, but it had a rhythmic integrity that carried the day (though I found his occasional tempo rushes a bit baffling). The Andante was played with sweet nonchalance, masterfully songful in the best of bel canto traditions. The final Allegro assai was again full-blooded and free, with a climax whose intensity felt fully “old school” – though not necessarily in a bad way.

Bach’s E-major Concerto began on the moderate side, with its aria-like Allegro seeming more garrulous than usual. The Adagio carried a sustained sense of melancholy, with full-throated solo playing in the lower register, and the finale (Allegro assai) dragged a bit but was cheerful and charming nonetheless. Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony began traditionally but picked up steam and mostly grabbed the attention of even the most jaded of listeners. Ensemble was not always perfect at the outset, but the musicians played with a refinement and grace one rarely hears stateside – more reasoned and tempered. Agogics were gentle and relaxed, sonorities were rarely rough or hard-edged (except for the occasional piccolo blip). Pizzicato passages were full and rich, and the finale tempo (which in the best of performances is an outgrowth of the Scherzo’s tempo) was nicely gauged for a logical, forthright conclusion.

To reach Paul Horsley, performing arts editor, send email to phorsley@sbcglobal.net or find him on Facebook (paul.horsley.501).

[slider_pro id=”2″]

[slider_pro id=”3″]

Features

Karen Paisley and the board of directors of the Metropolitan Ensemble Theatre have an urgent message for Kansas City theatergoers: We’re still here. Ten months after what appeared to be a…

December is filled with choral concerts, and in the coming weeks nearly all of the operational non-profit choirs — not to mention dozens of choruses hosted by places worship —…

For more than five centuries, European settlers went to extravagant lengths to erase Native American tradition, culture, and even language from the face of North America. The effect was devastating…